Chapter 6

Points of View and Assumptions

Bottom Line Up Front

Critical thinking requires an in-depth investigation of points of view and assumptions that influence decision making and behavior. Not taking time to address these two critical-thinking elements can severely degrade an analysis. Points of view (perceptions, world views) influence the assumptions and beliefs actors bring to a situation, which in turn influence the actors’ thought processes leading to decisions and behaviors. In identifying an actor’s points of view, the analyst draws heavily on the field of psychology. With points of view uncovered, a systematic process then is used to identify assumptions. Finally, actor beliefs—the underlying causal mechanisms supporting assumptions—must undergo a robust critical analysis.

Defining Points of View and Assumptions

With the initial information searches and context development completed (Chapter 5), the analyst next must investigate the points of view and assumptions at work in their analytic project. When analyzing human decisions, human behaviors, or human conditions, the analyst must understand the adversaries’ (and their own) points of view and assumptions. These create focus or orientation that allow a person to develop a comprehensive perspective on an issue.1 Assumptions emerge from an actor’s points of view and are something often taken for granted and are seldom revealed by those holding them. People use assumptions to interpret the world around them and condition their thinking and behavior.2 Thus, it is important for analysts to investigate points of view and assumptions in tandem before continuing in their analytic project.

Scholarly literature provides a number of definitions, characteristics, and effects of points of view and assumptions. This chapter explains some of their differences, presents the roles of points of view and assumptions in security analysis, and offers a systematic process for their evaluation. The process for assessing points of view starts with an understanding of the field of epistemology or the study of knowledge. As detailed in Chapter 3, a person’s knowledge base consists of information compiled since birth from sources of authority, faith, common sense, intuition, empiricism, rationalism, and science. This knowledge is imparted over time from family, friends, education, media, religion, culture, and the person’s own observations and experiences. Points of view result from combining this knowledge with logic and reasoning to develop perceptions, assumptions, and beliefs; that is, their understanding of how the world works. A points-of-view analysis allows the determination of how an adversary obtained and normally uses their knowledge on a particular topic. For example, an adversary using mainly intuition will have different points of view than those who rely primarily on science in their thinking. The development of points of view takes place in a person’s mental model, which is influenced by a number of cognitive filters. These filters do not guarantee the validity of a person’s points of view because they often are subject to misinformation, heuristics (cognitive biases), informal logic fallacies, and other mental influences. Points of view may be evaluated as true or false, justified or unjustified, good or bad, or useful or useless. The first challenge is to identify the points of view and then assess how they may manifest in a person’s decision making or behavior. Once points of view are identified and assessed, they help reveal the assumptions and beliefs that influence the person’s decisions and/or behaviors in a particular situation.

Analyzing points of view and assumptions includes aspects of both agency and structure (Chapter 3). Agency analysis, often called leadership analysis in the security community, looks closely at the individual characteristics of agents or actors (leaders, decision makers) or small groups of agents or actors (such as a ruling oligarchy) to help explain and predict decisions and behaviors in a situation. For intelligence analysis, the agents may be the leaders of foreign states, terrorist groups, or organized crime syndicates, among others. For policy analysis, the agents analyzed may be leaders of foreign states or those within their own state, in addition to foreign or own-state organizations or bureaucracies who may or may not concur with policy analysis recommendations. Structural analysis uncovers the political, organizational, bureaucratic, resource, and other constraints placed on leaders in decision-making situations. In assessing structure, the analyst must consider the laws, regulations, and rules, bounding or restricting the adversary’s decision making. These structural components are found in constitutions and supporting laws and regulations, international treaties, conventions, agreements, organizational and bureaucratic regulations and rules, and societal rules, both formal and informal, that prescribe acceptable behavior.

Scholars often find it challenging to combine aspects of agency and structure in the same analysis. U.S. foreign policy researcher Valerie Hudson offers that rule-based analyses have the potential to provide a flexible framework for integrating different theoretical approaches that employ both agency and structure.3 This includes building aggregate models for applying theories that emphasize agency and structure at different levels of analysis—individuals, organizations, cities, states, and regions. This chapter combines a rule-based, structural theoretical approach with agency analysis techniques that apply across multiple levels of analysis. This approach starts with development of a structural model of political culture that is built within a rule-based framework (Appendix III). This is followed by a more robust points-of-view model that combines the structural model with an agency analysis framework. The chapter concludes with an assumption analysis process to identify and assess assumptions and beliefs.

Points-of-View Analysis: Structure

Appendix III provides a starting point for assessing the points of view of states, societal groups, and individuals, where decision making and behavior are structurally constrained by their political cultures. To do so, this appendix develops a theory of political culture as a key component of points-of-view structural analysis and it reveals both the rule-based structures and the empirical conditions that correlate with different political cultures found in world states. By delineating the structure within which decision makers operate, the theory helps explain and predict political and economic behaviors and societal conditions not only in states, but also in organizations and other societal groups. The general terms of society or societal groups encompass levels of analysis below the state to include towns, cities, counties, corporations, departments, organizations, bureaucracies, and others. The analysis of individual states or societal groups often is a main focus of security analysts whose portfolios include political- military analysis or those assessing threat groups such as terrorists or organized crime syndicates.

Appendix III develops three main types of political cultures: egalitarian, individualistic, and authoritarian. Egalitarian political cultures are the most modern, including states that are mature, strong democracies. States and societal groups with egalitarian political cultures strive for the “good of society.” Individualistic political cultures are the next most modern, including states that are new, transitional, or weak democracies. States and societal groups with individualistic political cultures strive for the good of the “individual,” which is defined as specific individuals (government and corporate leaders) and special interest groups (large corporations, lobbying groups, etc.). Authoritarian political cultures are the least modern and include a variety of authoritarian states and societal groups (autocrats, dictators, oligarchs, etc.). States and societal groups with authoritarian political cultures strive for the good of the “leaders and elites.” Lastly, Appendix III details the characteristics of each of these political cultures.

Keep in mind that political cultures both establish its members’ expectations and place constraints on its leaders. Whether analyzing one state or societal group or comparing two or more states or societal groups, it is important to assess their political cultures. The assessment aids in explaining the situation under analysis or assist in predicting future actions. It also is important for analysts to assess their own state or organization’s political culture, as this helps avoid the stereotyping bias where analysts assume that other states or societal groups will act in the same way as their own. States or societal groups with different political cultures likely will behave quite differently in similar situations. Additional information searching (Chapter 5) likely is required to fully understand the empirical conditions of the political culture in a particular state or societal group.

Points-of-View Analysis: Agency

Both agency and structure are important components in assessing points of view that influence decisions and behaviors. This section addresses agency factors specific to agents (actors) at the individual and group levels of analysis. This type of analysis is referred to as leadership analysis in the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC). Some IC agencies have offices dedicated to leadership analysis. These offices provide policy makers an understanding of the leaders and other officials, some of which are adversaries, who they meet during the course of their world travels and meetings. This understanding allows policy makers to better assess the character of leaders and officials they meet and assess their points of view as an aid to diplomatic negotiations and security decisions.

To facilitate the following discussion on how agency and structural factors combine to both affect points of view, Figure 6.1 provides an abstract decision- maker mental model. This model assists in determining how decision makers (or leaders) develop their lens on the world, which includes their points of view and assumptions. The mental model starts with the knowledge and information a leader possesses on the situation, including which epistemology the leader primarily uses to make decisions. The leader’s knowledge and new information then passes through a series of cognitive filters described in this chapter. The first filter in Figure 6.1 establishes the expectations and structural constraints placed on the leader by the political culture of states and societal groups (Appendix III). Other filters described include biographic, cognition and reasoning, physical and mental states, emotions and attitudes, situation and politics, leadership style and personality, and group influences. The filters at work in any decision process will vary by situation, but will largely include the filters described in this chapter. Each filter will not; however, have the same influence on the leader’s final lens on how the world works. Some filters may have a strong influence and others may have little to no influence, all depending on the situation at hand and the individual leader.

Many of the filters discussed below come from the field of psychology, in particular the sub-field of cognitive psychology. Political psychologists, especially those specializing in foreign policy and security studies, make extensive use of cognitive psychology theories to help explain and predict security-related behaviors of foreign leaders.4 Law enforcement criminal psychologists (also known as profilers) use cognitive psychology to assess persons of interest and suspects during investigations. Assessing the mental model filters and their influences on decision making in a particular situation require in-depth information searches. Foreign leaders and persons of interest and criminal suspects in law enforcement investigations seldom will agree to in-person psychological interviews or batteries of psychological tests. The analyst; therefore, must develop the content of filters from statements, speeches, writings, and actions; or from observations from those with access to the person under study. Content analysis (Chapter 5) is a common method to assess peoples’ psychological traits. One problem with this method concerns counterfeit and hidden traditions; that is, when people say or write one thing for public consumption (their counterfeit tradition), and then act in a completely different manner (their hidden tradition) because of their hidden motives.5 It also is common for senior leaders to have speechwriters and ghostwriters draft what they eventually say or write for public consumption, which can lead a content analysis to uncover the filters of the speechwriters or ghostwriters and not necessarily of the leader under study. In the end, it usually is better to focus on what leaders do and to be suspicious of what they say or write.

Psychobiography is the term used to signify investigations of the experiential, cognitive, and emotional factors that influence a leader’s points of view and affect their decision making and behaviors. Psychologists often generate psychobiographies of past (usually deceased) leaders or interesting people where there is significant literature or personal observations of the subjects. Security analysts, who are not usually psychologists, are challenged with generating psychobiographies on current leaders where the literature and personal observations of the subjects are limited. Strategic psychobiographies delve deep into the life histories of subjects and could take considerable time to complete. Operational and tactical psychobiographies address the decision making and behaviors of the subject in a current situation where there are likely time constraints. It is recommended that strategic psychobiographies be completed for key leaders in an analyst’s portfolio in advance of operational or tactical situations. The following discussion identifies the many factors (or filters) a security analyst may employ to populate the Figure 6.1 abstract mental model and create psychobiographies in support of points-of-view analyses.

Biographic filters. U.S. intelligence agencies collect and compile biographic material on foreign political and military leaders. The most basic material compiled may include information on the leader’s childhood, family relationships, education, career experiences, successes, and failures. In foreign policy activities, the diplomatic training or regional and world experiences a leader possesses also are investigated.6 More in-depth information also may be compiled on other aspects of a leader’s background to include mentors, hobbies, recreational activities, favorite food and drinks, sexual proclivities, extramarital affairs, abuse of power, and criminal activities. Law enforcement analysts use biographic analysis to assess suspects, including the leaders and their most influential lieutenants in criminal organizations. Much of the basic information on foreign leaders is available publically, while additional information can be provided by human intelligence (HUMINT) collectors trained in gathering biographical information through observations of and meetings with foreign political and military leaders and those with access to the leaders.

In the 1970s, U.S. political psychologist Jerrold Post was one of the founders of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Office of Leadership Analysis.7 He offers a number of important factors to uncover when conducting biographic research. First, to uncover potential influences on the leader’s behaviors, he created a timeline of national and world events that occur during a leader’s life. Post then looked closely at the leader’s family saga, including birth order and relationships among siblings. He also sought to answer a number of other questions: Did the family immigrate from another state or region? Is the family wealthy and how has the wealth varied over generations? Were family members war heroes? Did traumatic deaths occur in the family? Who were the leader’s early heroes? What were the leader’s early dreams and goals? What were the leader’s early successes and failures? These and other biographic data are instrumental in assessing leaders’ points of view.

Cognition and reasoning filters. These filters go to the heart of how the leader processes information and reaches conclusions. The analyst must investigate whether the leader’s cognition displays the tendencies in Figure 2.1 listing characteristics of good critical thinkers, or the Figure 2.2 tendencies of poor thinking. This includes determining the leader’s tendencies toward System 1 or System 2 thinking (Chapter 2 and Appendix II). Nobel Prize laureate and U.S. cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman argues System 1 thinking is influenced by one or more heuristics (or cognitive biases); see Appendix II for Kahneman’s list of the most prevalent heuristics.8 System 1 thinking is very intuitive (sometimes called relying on “gut feelings”) and governs most everyday human behavior. System 1 thinking usually is adequate for most day-to-day decision making; but, when more complex situations arise, System 2 thinking is required. In the Cuban Missile Crisis (see Box 2.1), President Kennedy and his advisors shifted from a System 1 thinking approach on the first day of their crisis deliberations, to using a System 2 thinking approach in following days. This was while Russian Premier Khrushchev was primarily using System 1 thinking. Most of the situations security analysts investigate will call on leaders to use System 2 thinking; so, it is important to understand a leader’s abilities and tendencies to engage in this more robust type of thinking.

Figure 2.3 lists the common heuristics found in security analysis. The most common societal-wide heuristic is confirmation (or affirmation) bias, where the person accepts only information that supports a preformed point of view and rejects contrary views or evidence. Cognitive dissonance is one explanation for why a person employs confirmation bias; it defines situations where conflicting information about a person’s existing points of view, past knowledge, or conflicts between their beliefs and actions, are present in a person’s mental model. Rather than work or think through the mental conflict, confirmation bias can lead people to reject new information to relieve mental and emotional distress.9 Analysts must evaluate if their subjects display the tendencies of confirmation bias, other common biases in Figure 2.3, or other heuristics from Kahneman’s more extensive list in Appendix II.

Reasoning is defined as the capacity for humans to know, rationalize, and understand their world.10 Good reasoning entails the combining of information (data, evidence, etc.) and logic to reach a rational or otherwise valid conclusion. There are a number of conditions that can derail good reasoning and result in the poor-thinking tendencies, as shown in Figure 2.2. Scholarly experiments demonstrate that humans are bad at evaluating information.11 Humans also are bad at employing joint (conditional) probabilities in their reasoning (Chapter 7), often leading to a misunderstanding of risk in a situation.12 In some cases, a leader may rely on misinformation or outright lies, including when the leader is the source of the misinformation or lies, because a person’s reasoning can create a view of reality that is untrue or invalid. For more details on leaders whose points of view are influenced by false realities, see the discussion of Critical Belief Analysis later in this chapter.

Ideally, a leader’s thought processes and communications would use logical argumentation, which is discussed in Chapter 9. This requires that leaders reach their contentions (findings, key judgments, conclusions, and/or recommendations) by accurately combining valid information and logic, while also addressing any alternatives and objections to their contentions. Analysts must not only assess how the leader employs information and misinformation within their statements and arguments, but also should watch closely for the insertion of informal logic fallacies in their reasoning. Appendix I provides a summary of the most common informal logic fallacies. One widely used informal logic fallacy is the part-to-whole fallacy, which asserts that what is true of part of something also must be true of the whole thing. This is seen when the leader uses only a few pieces of situational information or misinformation to generalize to a much larger population. When leaders make statements such as “many people think,” “I have heard,” or “so and so told me,” it is usually an indicator that a part-to-whole fallacy is about to follow. The type of fallacy is behind the political discourse that claims “all Muslims are terrorists,” which is not true because only a few Muslims have been shown to be actual terrorists. The part-to-whole fallacy tends to ignore situational context and violates the rules of sampling theory (Chapter 3).

Physical and mental state filters. Cognition operates within the context of a leader’s physical and mental states, which can severely affect mental acuity. Stress, use of both licit and illicit drugs, physical pain, fatigue, and age, all can affect a leader’s ability to think and reason clearly. Studies have shown leaders are often at their best when under moderate stress, but their mental acuity decreases during periods of low or high stress.13 High levels of stress, and any associated lack of sleep, can lead to fatigue and confusion. There is limited information, but significant rumors, about some leaders using illicit drugs. It is more common; however, for them to abuse licit drugs such as alcohol, caffeine, nicotine, as well as over-the-counter and prescription medications. President Richard M. Nixon was known to abuse alcohol while also self-medicating with a prescription medication for seizures, in addition to taking other prescription medications to fight depression and mood swings. The result of this cocktail of alcohol and prescription medications could cause memory loss, irritability, and confusion; which would support a mental state of paranoia that Nixon displayed during the Watergate Crisis.14 Physical pain and treatment for the pain also can affect a leader’s mental acuity. President John F. Kennedy used steroids and high- dose pain medication to help manage his back pain from a World War II combat injury.15 Even though Kennedy’s legacy is one of good decision making, the pain and treatments for his back pain no doubt affected his mental acuity. Finally, with age comes experience and knowledge, but leaders of advanced age also can suffer physical and mental afflictions common to the elderly.

Both temporary and permanent mental illness also can affect a leader’s decision making. A 2008 U.S. Department of Defense study concluded that Russian leader Vladimir Putin suffered a form of high-functioning autism known as Asperger’s syndrome, which affected his decision making; of course, the Russians denied this diagnosis.16 Mental illnesses in leaders can be expected to match the types and frequencies found in the general population. Scholars have found certain mental illnesses, including narcissism and paranoia, are overrepresented in the population of world leaders.17 An unhealthy obsession with power and control is estimated to affect around 13 percent of world leaders.18 The stress of leadership may cause a leader’s tendencies toward mental illness to advance to a pathological state. Box 6.1 provides an example of mental illness that created a pathological state in Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.

Box 6.1 | Saddam Hussein: Narcissistic Pathology 19 |

From the 1980s to early-2000s, as Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein gained more and more power, his mental illness appeared to become pathological and seemed to affect his powers of judgment. His inability to admit ignorance restricted his ability to learn by absorbing new information. He could not accept dissent to his views or behaviors, leading to his receiving no dissonant information from his advisors. Saddam’s power fantasies, lack of impulse control, willingness to use force, absence of empathy, and lack of a conscience warped his decision making. What was good for Saddam became the defining national interest for Iraq. With his mental acuity diminished by his narcissistic mental state, Saddam misperceived the diplomatic signals sent by the United States prior to the U.S. 2003 invasion of Iraq, leading to the downfall of his regime. | |

As seen in Box 6.1, narcissism in particular may foster an acute mental state in some leaders, because it can result in a leader who is willing to take any risk or pay any price to obtain and maintain a leadership role. When narcissism advances to a condition of malignant narcissism, it likely will have significant effects on a leader’s mental acuity. Psychologists view malignant narcissism as a combination of an antisocial personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, and tendencies toward sadism, aggression, and paranoia. Figure 6.2 provides a summary of traits found in those with malignant narcissism, a condition often found in leaders in authoritarian political cultures in addition to some democratic leaders. Many leaders, even in democratic societies, may exhibit one or more of the Figure 6.2 traits; but, when a number of these traits are present, a diagnosis of malignant narcissism likely is appropriate and can help explain a leader’s points of view and better allow prediction of future decisions and behaviors.

Figure 6.2 | Malignant Narcissistic Traits 20 |

Sees the world in black and white or us versus them. Preoccupied with fantasies about success and power. Unable to accept or deal with criticism. Tends to lash out if feeling slighted. Takes advantage of others to get what they want. Overly concerned with their physical and reputational appearance. Expects special treatment. Lacks empathy for feelings or suffering of others. Possesses an inflated sense of self. Lacks impulse control. Lacks interest in apologizing unless it benefits them. Feels they deserve the best of everything. Monopolizes conversations and lacks patience to listen to others. Mistreats those whom they perceive as inferior. Hides insecurities and possesses a weak sense of self. Fails to take responsibility and blames others for his/her own misbehavior. | |

Emotion and attitude filters. System 1 thinking takes place subconsciously and often involves emotions and attitudes. Combining emotions with use of heuristics (or cognitive biases) and poor reasoning (such as informal logic fallacies) likely will result in degraded thinking. Emotions may be either positive or negative motivators of a leader’s actions; but, once emotions take hold of decision making—even when faced with conflicting information—the person may still act on those emotions. Box 6.2 describes a positive emotion-based action that took place in World War II.

Box 6.2 | Emotion-Based Decisions: General Douglas MacArthur |

The December 1941 Japanese invasion of the Philippines caused U.S. General Douglas MacArthur to evacuate his family and staff to Australia where he made his now famous statement, “…I will return.” As commander of the allied Southwest Pacific Area, MacArthur worked closely with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps forces commanded by U.S. Navy Admiral William “Bull” Halsey.” With Halsey’s forces, plus MacArthur’s Allied and U.S. Army forces, MacArthur directed the grueling 1941-1943 Solomon’s Island Campaign and combat operations across New Guinea to dislodge the Japanese occupiers. MacArthur then faced an emotion-based decision. After the Solomon’s Island Campaign, Commander of the Central Pacific Area Admiral Chester Nimitz wanted to continue the allied “island-hopping” campaign to conquer Japan first and leave dealing with the Philippines and its 500,000 occupying Japanese troops for later. MacArthur insisted the Allied forces first take the Philippines as he had turned his often-repeated statement “…I will return” into a personal mantra. He frequently repeated that mantra to his staff, combat forces, and in public speeches and media interviews. He considered invasion of the Philippines a case of personal honor to follow-up on his promise to the Philippine people. Washington D.C. war leaders backed MacArthur, so Nimitz dutifully diverted his naval and marine forces to assist with the Allied invasion of the Philippines. This incident shows how emotions can drive important war decisions. In MacArthur’s point of view, the invasion of the Philippines was of the highest priority at this point in the war. In the end, the invasion was successful, and MacArthur’s emotions could be seen as a positive motivator (from the Allied view) toward victory. Emotions also can negatively affect a person’s tolerance for risk, as in this situation when MacArthur was willing to take the risk of facing a large opposing Japanese force where many Allied soldiers and sailors likely would die. An unintended consequence of the Philippine’s invasion saw the U.S. Navy effectively destroy the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in several sea battles around the Philippines. This facilitated successes in the later resumed “island- hopping” campaign toward Japan where there was now a limited threat to U.S. invasion forces from the IJN. | |

Emotions also can have significant effects on points of view by affecting attitudes. When a leader brings personal feelings of negativity to their official positions, it can lead to a dysfunctional orientation for the entire organization.21 A leader’s negativity often originates in childhood (see biographic filter above) and fosters unhelpful compulsions, addictions, and neuroses throughout their relationships with others. When negativity flows from the leader, it can contaminate the organization and create an atmosphere of cynicism and general malaise. Those with negative attitudes usually are motivated to help themselves or maintain the status-quo. Often, “negaholics” are not easily identified because they may appear as the perfect person with an extremely strong work ethic; but inside, they are driven and tormented.22 Negative emotions can foster grievances, hate, anger, and rage, among others, and can result in negative actions. Negative leaders likely will ignore risk factors as they may take actions based in revenge, vindictiveness, or spitefulness. Fear also is a strong, usually negative, motivator that can lead to a failure to act or to act impulsively. Both positive and negative emotions often influence a leader’s attitudes and may create more confidence than warranted in resultant actions. Attitudes lead to points of view generated by the memories, emotions, values, and beliefs a person brings to a situation. Different attitudes may govern different situations, and attitudes often add energy to the effects of other filters in the Figure 6.1 mental model.

U.S. political scientist James David Barber studied U.S. presidents and developed a model of leader personalities, which works equally well for evaluating attitudes for any leader.23 His model contains two axes—active-passive and positive-negative—resulting in four categories of leaders. The active-passive axis evaluates the leader’s motivation and energy levels and their sense of how personal effort can make a difference. The positive-negative axis evaluates the leader’s motivations for seeking office and overall outlook on life. Positive leaders tend to be optimistic, trusting, confident, and driven by a joy for their work. Negative leaders tend to be pessimistic, suspicious, needy, and feel obligated to conduct the work. The four categories of leaders that Barber developed are listed below in order of best to worst leaders:

Active-positive leaders are not driven by twisted or dark motives and are willing to work hard to make improvements because they are flexible and will reverse course when things go wrong as they are not constrained by a rigid ideology. Their motivation surrounds a sense that they should seek policies that produce the results they desire. Barber considered these the best leaders, which included U.S. Presidents F.D. Roosevelt, Truman, and Kennedy.

Passive-negative leaders take office out of a sense of obligation or duty, not for power and control. They may have a difficult time creating significant change due to their lower energy and activity levels. Barber considered these the second-best type of leaders, which included U.S. Presidents Coolidge and Eisenhower.

Passive-positive leaders focus on issues of affiliation and acceptance. They are dependent on others for reassurance, support, and even direction. Due to the leader’s emotional neediness, others often are willing to take advantage of them because the leader will turn a blind eye to their own and others’ excesses. Barber considered these the second-worst type of leaders, which included U.S. Presidents Taft, Harding, and Reagan.

Active-negative leaders are compelled to office and power by deep-seated feelings of inadequacy as well as a fear of humiliation and ostracism. They often are rigid in thinking and actions, especially when threatened. They cannot relate to others because they lack empathy and personal warmth. These leaders often are feared but not loved, and they know it. They are willing to circumvent rules, laws, and conventions to increase their power. Barber considered these the worst leaders, which included U.S. Presidents Wilson, Hoover, Johnson, and Nixon.

Situation and politics filters. Both the specifics of the situation at hand and politics may affect a leader’s points of view and related decision making. For day- to-day, minor issues and situations, the leader may have little interest in the issue/situation and delegate the decision making to subordinates. In major strategic situations where time is not a factor, for example deciding major policies, the leader may take a greater interest. In the United States, the Figure 4.1 U.S. National Security Council process is designed to bring the highest leaders into the decision making. In operational or tactical crisis situations that affect a state or society’s most vital interests, senior leaders and their closest advisors may be called on to make decisions under severe time constraints and with incomplete information, thus making the situation more ambiguous. Time- constrained operational and crisis situations also may not allow time for the analytic and advisory support needed for good decision making. Leaders also may have little time for their own deliberations. In crisis situations, for example, it is likely the leader will rely more on their intuition and emotions in making decisions. In the Box 2.1 summary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, it is shown how the crisis unfolded over a 13-day timeframe in which President Kennedy first had to deal with incomplete information, but later gathered more information and brought additional advisors into the deliberations.

Politics drive modern societies and play a significant role in any leader’s decision making; this includes both domestic and international politics. The old adage that the “primary motivation of politicians is to gain and retain office (power)” is quite true and has major influence on a political leader’s decisions. U.S. political scientist Howard J. Wiarda developed a political process model to explain how leaders are influenced by domestic political actors as they make decisions.24 His model, similar to the Figure 6.1 decision-maker mental model, starts with the structure of a state or society’s political culture (Appendix III). In descending order of saliency, Wiarda then offers how a leader can be influenced by public opinion (more so just before elections), media, interest groups, political parties (both the leader’s and the opposition), think tanks, social relations (family and friends), legislators, government departments, and close advisors. These domestic actors often seek influence on both domestic and international issues. When working in the international arena, international political actors with significant influences come from non-governmental organizations (NGOs such as Amnesty International, etc.), international governmental organizations (IGOs such as the United Nations, European Union, NATO, etc.), and foreign state leaders. Often a U.S. leader will establish close personal relationships with some foreign state leaders, which also may affect their decision making. Security analysts must investigate the influences of each domestic and international actor to explain past behaviors, current points of view, and predict a leader’s decision making. In the Box 2.1 summary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, President Kennedy was being advised by several domestic actors and also took counsel or coordinated U.S. plans with key foreign leaders, including the United Nations, NATO, and the Organization of American States, before making his final decisions.

Leadership style and personality filters. These filters also influence points of view and decision making. There are a number of definitions and theories of leadership. The definition used herein is “[l]eadership is a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal—something they [the group] would probably not do on their own.”25 A common measurement of leadership effectiveness offers that a successful leader is one who: (1) leads a group to achieve (or nearly achieve) the common goal, and (2) the group is willing to work with the leader toward the same or similar goals in the future. A leader can employ a number of personal power bases to influence a group. Figure 6.3 depicts power bases, which a leader can use in varying degrees depending on the situation and group to be influenced.26 Reward power is the ability of the leader to reward group members for good efforts. Punishment or coercion power allows the leader to deal with group members who are not contributing to goal attainment. Authority or position power is the ability of leaders to rely on their superior rank in a situation to influence the group’s efforts. Expertise power is the amount of training, education, and experience the leader brings to a situation and that is recognized by the group. Referent power is the influence a leader derives from the group’s evaluation of the leader’s likeability and the leader being recognized as a good role model. Especially important in policy analysis, it is essential for analysts to assess a leader’s style to help explain and predict their points of view, decision making, and behaviors.

Good leaders do not have one leadership style. Situational leadership theory offers the leader must be flexible and match their leadership style to the readiness of the group (subordinates or peers) being lead.27 This theory offers that the leader’s style; i.e., use of power bases, will vary depending on the situation and characteristics of the group being lead. For example, if the group is not competent (not trained or experienced) but motivated, the leader may use a style relying on a combination of his/her authority, expertise, and reward powers to increase competency and bolster the group’s motivations to achieve the common goal. If, on the other hand, the subordinates are competent but not motivated, the leader may rely on a style combining authority and punishment powers, while building referent power to better motivate the group toward the common goal. As both competency and motivation increase among group members, the leader should adjust the leadership style to apply greater levels of their expertise, reward, and referent powers, while reducing the use of authority and punishment powers (this level of power used is depicted in Figure 6.3). If a situation arises where the group being lead has the same or similar levels of authority power (i.e., a peer group of military officers), then the leader is challenged to employ both expertise and referent power to assist the group in achieving a common goal. Unfortunately, a majority of leaders are not flexible in their use of the power bases and will demonstrate tendencies of a single leadership style ranging from passive leaders (reward, referent power dominant) to authoritarian leaders (authority, punishment power dominant). It is important for analysts to identify both flexible (situational) and single-style leaders because leadership styles will provide insights to leaders’ points of view, decision making, and behaviors.

Tied closely to leadership style is a leader’s personality traits. The Figure 6.1 mental model output of the leader’s lens on the world (points of view, perceptions, assumptions, beliefs) is influenced significantly by the leader’s personality filter. There are a number of definitions of personality, most of which agree that a leader possesses a number of traits. These traits include a leader’s distrust of others (internally and externally), their ability to conceptualize the complexity of the world and the current situation, the loyalty a leader shows to social groups (state, organizations, political party, close advisors, family), emotional stability, ability to control impulses, and application of focus and energy for task completion.

There are a number of models for assessing personality. One of the most widely used is the Myers and Briggs Type Indicators, which normally measure personality through a test of people under study.28 An estimate of a person’s Myers and Briggs personality type also may be made from direct observations and interactions with the person. For example, HUMINT collectors have been trained in how to recognize different personality types to facilitate their source recruitment and elicitation efforts.

The Myers and Briggs types offers that different personality types influence how a person perceives the world and how they make decisions. Assessing a person’s personality type helps determine their interests, reactions, values, and motives. The Myers and Briggs personality types are determined across 4 axes as explained below:29

Favorite world: Does the person prefer to focus on the external world or their own internal world? This is typed as either Extraversion (E) or Introversion (I).

Information: Does the person focus on basic information as presented or seeks additional information, which they prefer to interpret and add meaning? This is typed as either Sensing (S) or Intuition (N).

Decisions: When making decisions, does the person prefer to first look at logic and consistency or instead first consider people and special circumstances? This is typed as either Thinking (T) or Feeling (F).

Structure: In dealing with the outside world, does the person prefer to make a quick decision or to stay open to new information and other alternatives? This is typed as either Judging (J) or Perceiving (P).

Myers and Briggs’s personality types are designated by using four letter codes, resulting in 16 different types. For example, an ENTJ type would have the personality traits of Extroversion, Intuition, Thinking, and Judging. Myers and Briggs offer ENJT types indicate people who are:

“Frank, decisive, assume leadership readily. Quickly see illogical and inefficient procedures and policies, develop and implement comprehensive systems to solve organizational problems. Enjoy long-term planning and goal setting. Usually well informed, well read, enjoy expanding their knowledge and passing it on to others. Forceful in presenting their ideas.”30

For more information on the Myers and Briggs Type Indicators, including on how to assist and evaluate personality types, analysts should see the web site at https://www.myersbriggs.org/.

U.S. political psychologist Margaret Hermann provides another model for assessing leader personalities. Using a combination of word-count and thematic- content analysis methodologies (Chapter 5), she assessed the personalities of over 200 world political leaders and heads of state using seven personality traits.31 She looked specifically for leaders’ traits related to: (1) beliefs in their ability to control events, (2) need for power and influence, (3) conceptual complexity, (4) self-confidence, (5) task orientation (problem focus or relationship focus), (6) distrust of others, and (7) nationalism (in-group bias). The content analysis resulted in development of three general characteristics of leader orientations toward: (1) constraints (challenge or respect), (2) information (open or closed to new information), and (3) problem focus. These three characteristics led Hermann to define eight personality orientations:32

Expansionistic: challenges constraints, closed to information, focuses on expanding their power and influence.

Evangelistic: challenges constraints, closed to information, focuses on persuading others to accept their message and join their cause.

Incremental: challenges constraints, open to information, focuses on maintaining their maneuverability and flexibility while avoiding obstacles that could limit both.

Charismatic: challenges constraints, open to information, focuses on achieving their agenda by engaging others in the process and persuading them to act.

Directive: respects constraints, closed to information, focuses on personally guiding policy along paths consistent with their own views while working within the norms and rules of their current position.

Consultative: respects constraints, closed to information, focuses on monitoring a problem situation to see what influential constituents will support or at least not actively oppose.

Reactive: respects constraints, open to information, focuses on assessing what is possible in the current situation given the nature of the problem and what important constituencies will allow.

Accommodative: respects constraints, open to information, focuses on reconciling differences and building consensus, empowering others, and sharing accountability in the process.

Whether employing Barber’s active-passive and positive-negative categories, Myers and Briggs’ Type Indicators, or Hermann’s personality orientations, or other models for assessing personalities, it is important to include personality in psychobiographies. These assessments play an important role in assessing a leader’s lens on the world and their points of view and assumptions.

Group influence filters. Agency analysis includes assessing the influence groups impart on an individual, social group, or state’s points of view and decision making. This includes groups that advise a central decision maker or groups who vote to make decisions. Even the best leaders cannot make all decisions themselves, but require advisors who collect and analyze information, prepare alternatives, and recommend actions. States and societies with authoritarian political cultures—and some individualistic political cultures—often employ close advisors who support a single, central leader (or decision maker). These close advisors do not usually have agendas of their own; but instead, focus on assisting the leader in making decisions. Individuals that make up groups of close advisors usually are selected because of their close relationship with the leader or have similar points of view to the leader. This form of group decision making would occur if a U.S. president consulted only with members of their White House staff and did not consult representatives from other government departments or agencies. Analysts should learn about the group decision-making process that adversaries employ. Normally, a psychobiography would be required for each group member; however, this presents a challenge in collecting information, both in the large amount of information required to complete multiple psychobiographies and in gaining details about the group processes at play. This challenge is even greater when some of the most influential group members maintain a low public profile—some to the point that their identities will be unknown.

The inter-relational dynamics of small groups of close advisors or groups who vote on decisions can be both positive and negative. When the group follows a critical-thinking framework—meaning they embrace actions toward good information searches, generate lists of alternatives, and conduct good analysis resulting in useable recommendations—it imparts positive effects on decision making. Unfortunately, many small group deliberations are dysfunctional and lead to degraded results. This is mainly due to the conflicting personalities of group members, which can cause members to take on roles such as being advocates for a particular action, cue-takers supporting what other important members offer, or brokers who try to foster cooperation and consensus among group members.33 Those who are silent in the deliberations effectively signal their approval of the final results. At times social cohesiveness of the group becomes the primary purpose of the group deliberations rather than effectively solving the problem at hand. Some group members (cue-takers) often will support the view of the group leader or most aggressive member(s), while others with different perspectives, alternatives, or recommendations simply remain silent to facilitate group cohesion. U.S. research psychologist Irving Janis designated these dysfunctional group dynamics as “groupthink.” When groupthink is present, the standards for analysis and final decisions are usually of lower quality; i.e., the optimum decision likely is missed. For example, on the first day of the Cuban Missile Crisis deliberations, President Kennedy gathered his ExCom made up of both close personal advisors and the heads of several cabinet departments and military services. Even with this mix of advisors, groupthink was evident in the first day of the committee’s deliberations because the “hawks” took control of the discussions and pushed to attack Cuba and destroy the Soviet missile sites, while other advisors in the room remained silent (see Box 2.1).

When heads of government departments, agencies, or other organizations are part of the group decision process, it creates an expanded set of group dynamics. The U.S. National Security process (see Figure 4.1) is designed to coordinate the points of view of differing departments and agencies. Scholars use the government (bureaucratic) politics model to evaluate this structure of decision making. Different departments, agencies, and organizations come to the table with different missions, roles, practices, and perspectives. Leaders representing their home organizations engage in an interagency “political game” of bargaining and compromise, with each leader attempting to promote their organization’s interests. Each organization maneuvers to make their perspective the one accepted in the negotiations. Organizations also will compete in the interagency deliberations for additional resources and expanded missions. They will fight for primacy with larger organizations having the strongest jurisdictions in the issue area and attempt to take control of the deliberations. For example, on U.S. diplomatic issues, the U.S. State Department will expect to take the lead, but should be ready for other departments, especially the Department of Defense, to attempt to take control of deliberations. Overlapping jurisdictions often complicate the deliberations as several may see their organization as being the “lead agency” on the issue. In the United States, dozens of departments and agencies have jurisdiction in different aspects of the “War on Drugs,” making interagency agreement on related issues challenging.

Another set of group dynamics exists within individual organizations, which make many low-level decisions and execute both low- and high-level decisions. Scholars use the organizational behavior model to evaluate this structure of decision making by individual organizations. As mentioned above, individual organizations have their own missions, roles, practices, and perspectives. They are constantly seeking to expand their missions and roles and gain leverage for additional resources. Their perspectives usually differ from other organizations as they produce their own organizational cultures. Anyone who has worked in the U.S. joint military arena knows each military service has their own organizational culture. U.S. security analyst Carl Builder in The Masks of War analyzed the different cultures (styles) of the U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, and U.S. Army. He defined the essence of each service as displayed in their strategies and behaviors. Builder found that the U.S. Navy’s culture is steeped in maritime tradition as they seek to emulate the overwhelming world naval power previously displayed by the British Navy in the 18th and 19th centuries. The U.S. Air Force’s culture worships at the altar of technology. The U.S. Army’s culture sees their service as the protector of the homeland. Builder offered that these organizational cultures still drive the decision making and behaviors of the three U.S. military services.34

The organizational behavior model highlights how organizations are made up of resources (people, equipment, facilities, and funding), which they organize and manage through a set of standard operating procedures (SOPs). To evaluate an organization’s behavior (or perspectives), the SOPs must be identified, which sometimes are refined to make the organization more efficient. Making significant changes to SOPs, or creating new ones, usually is difficult. Situations of budgetary feast, prolonged budgetary famine, dramatic performance failures, and threats of organizational elimination, all tend to lead to major changes to SOPs and other organizational behavior changes. While SOPs define an organization’s range of actions, they also can be somewhat restrictive when new or unfamiliar actions are levied on an organization. For example, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the U.S. Navy was tasked to lead an Allied maritime quarantine of Cuba. The Navy did not have an SOP for quarantine, but instead interpreted the orders as a blockade, for which they did have an SOP. The blockade SOP called for stationing ships closer to Cuba and fostering aggressive rules-of-engagement to make Soviet submarines surface and to fire on Soviet merchant ships that did not stop for inspection. This was not; however, what President Kennedy wanted. So, the U.S. Navy was directed to establish a new quarantine SOP, which they did reluctantly. This new quarantine SOP called for U.S. and Allied ships to intercept Soviet merchant ships at least 500 miles from Cuba, and measures were implemented to avoid violent confrontations with Soviet merchant ships or military vessels. This new SOP met Kennedy’s goal of avoiding conflict and providing plenty of decision time as Soviet merchant ships approached Cuba.

When faced with a group decision process and its influence on leaders, the analyst first must determine the appropriate level of analysis. Is it primarily a small group of close advisors supporting a single leader? Is it a group voting on decisions? Is it a group of leaders of departments, agencies, or other organizations involved in a bureaucratic politics game? Or is the analytic focus on an individual organization driven by SOPs? Analysts investigating group decision dynamics should read deeply into the scholarly literature on the subject. In Foreign Policy Analysis, Hudson offers a more extensive discussion of group decision making.35 Janis’s Groupthink, and a large amount of follow-on literature, addresses the psychology of small group dynamics.36 In Essence of Decision, U.S. political scientists Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow provide details on the government (bureaucratic) politics and organizational behavior models.37

Insights from agency analysis. To identify the points of view, perspectives, assumptions, and beliefs that affect a security analysis requires a thorough investigation of both the structural and agency factors at play. The information requirements to conduct such a robust investigation can make this sort of analysis overwhelming; however, thoroughly considering the structural and agency factors will make the final results of the analysis more accurate and useful. Figure 6.4 is a checklist to assist with developing a complete psychobiography of leaders under study. Analyst(s) should use this checklist, within the existing time constraints and data available, to organize and record the information found and to help assess the points of view in a situation.

Scholarly research often focuses on only one or two of the Figure 6.4 psychobiography factors. It has been shown; however, that considering more than one of these categories can generate expanded insights to help explain and predict leader decisions and behavior as manifested in their points of view and assumptions. CIA leadership analyst Jerrold Post created a psychobiography methodology he named anamnesis that combines biographic material, leadership style assessments, personality assessments, and substantive belief identification (see next sections on assumptions and belief analysis).38 As one of the founders of the CIA’s Office of Leadership Analysis, Post and his staff provided U.S. national security leaders psychobiographies of world leaders for over two decades. This chapter advocates for a similar multi-factor approach.

Figure 6.4 | Points-of-View Analysis: A Psychobiography Checklist |

Sources of leader(s)’ knowledge____________________ Main epistemology(ies) leader(s) use(es) in decision making________________ Timeline of national and world events influencing leader(s)’ lives_____________ Analysis of leader(s)’ decision-making abilities/tendencies: ____Political Culture (Appendix III) ____Attitude Assessment ____Biographic Material ____Situational Factors ____Cognitive Assessment ____Political Factors ____Reasoning Assessment ____Leadership Style Assessment ____Physical State ____Personality Assessment ____Mental State ____Group Influence Factors ____Emotional Assessment | |

Assumption Analysis

As described above, points-of-view analyses helps uncover assumptions and beliefs. Assumption analysis entails techniques to identify and analyze the key assumptions at work in an analytic issue. The traditional approach to assumption analysis was first introduced in Chapter 3 and considers assumptions as theoretical propositions (or statements) taken to be true even though there is no information to prove or disprove them. Introduced in Chapter 7, modeling and theory building usually employ a number of assumptions about how the world works. In analytic interpretation and inference described in Chapter 9, assumptions are used to fill information gaps. Ambiguous or deceptive information often also causes the analyst to use assumptions to reach their findings. Analysis and decision making in security analysis are often confronted with uncertainties in information and logic, which must be filled with assumptions. Analysts must be aware that misunderstanding assumptions can invalidate analytic findings. The challenge for analysts becomes one of uncovering inconsistencies in the existing information and logic that comprise the assumptions, while searching for biases in both the agents under study and the analysts’ own thinking. They look for indications their agents’ or their own assumptions are valid (good, true, or justified). This is the traditional security analysis approach to assumption analysis. Analysts should know that invalid assumptions may result in customers who experience situational surprise leading to their inadvertently or unnecessarily moving people or operational resources.

An emerging approach to assumptions analysis calls for a robust analysis of the origins and content of assumptions and corresponding beliefs. This approach, which builds from the traditional approach, offers points of view generate assumptions that are supported by underlying beliefs. The previously discussed points-of-view analysis also is the starting point for this approach. After the assumptions of both the actors and analyst(s) in the situation are identified, the assumptions are categorized according to the role they play in the person’s thought process about a situation. The associated supporting beliefs for the assumptions then are identified and critically evaluated. Belief analysis considers the causal mechanisms underlying assumptions. It assesses whether specific beliefs provide the guidance the actor or analyst relies on the belief to provide, which then highlights differences between expectations and reality. In other words, beliefs lead to action, which then lead to outcomes (positive or negative). Belief analysis is not widely used in either academic or practitioner security analysis circles.

Identifying assumptions. This section offers a three-part approach for overcoming the challenge of identifying assumptions in the traditional approach. Assumptions exist in all human thinking, but are not readily identified. They usually consist of a cluster (web) of complex, interlocking key assumptions and supporting assumptions. The procedure for identifying assumptions starts with either individual analysts or groups of analysts employing a Four Ways of Seeing + Analyst technique to identify the key assumptions related to an adversary’s points of view. Second, supporting assumptions are developed utilizing an informed-brainstorming technique (Chapter 8). Third, both key and supporting assumptions identified are categorized to gain additional insights. This categorization may generate additional assumptions. Failing to identify key and supporting assumptions can lead to analytic failures. One significant failure occurred in the 2003 Iraq War.

When the United States and United Kingdom invaded Iraq in 2003, they promised ordinary Iraqis that life would get better after Saddam Hussein. But as one U.S. commander… found: “The concept of ‘better’ proved to be a terrible cultural misperception [assumption] on our part because we, the liberators, equated better with not being ruled by a brutal dictator. In contrast, a better life for Iraqis implied consistent, reliable electricity, food, medical care, jobs, and safety from criminals and political thugs.”39

Four Ways of Seeing + Analyst. This analytic technique for identifying different views of an issue has been used in the security and critical-thinking communities for many years.40 It allows the analyst or groups of analysts to delineate differing points of view and key assumptions for one or more actors using a simple matrix analysis technique shown in Figure 6.5. The blocks for two actors list their views of both the issue at hand and the views of other actors. There is also a final block for the analyst(s) to list their views, or the views of their home state or organization, about the actors and issues at hand. It is important that the analyst(s) assess their own views to uncover their own biases that may impact their analysis.

Figure 6.5 | Four Ways of Seeing + Analyst | |

Actor A: How does Actor A see the issue at hand? | Actor B: How does Actor B see the issue at hand? | |

How does Actor A see Actor B vis-à-vis the issue at hand? | How does Actor B see Actor A vis-à-vis the issue at hand? | |

How does/do the Analyst(s) see Actors A and B vis-à-vis the issue at hand? | ||

There seldom are just two actors involved in most issues. Figure 6.5 defines a dyadic (two-actor) scenario that is flexible and may be modified to include all actors involved in the issue. In a situation with only one outside actor (A), the second actor (B) could capture the views of the analyst(s) or their home state or organization. If there are more than two outside actors, then the figure would be expanded to Nine Ways of Seeing (3 outside actors), Sixteen Ways of Seeing (4 outside actors), or more. When there are more than two outside actors, a better analytic process would be to conduct a pairwise comparison (Chapter 9), where the Figure 6.5 dyadic model would be used to analyze each actor individually against each other actor. It can get complicated with more than two actors. Remember that the goal of the Four Ways of Seeing + Analyst analytic technique is to identify the “big picture” key assumptions (points of view and perspectives) of the actors and analysts involved in the research. From this, the analyst may proceed to identify additional key and supporting assumptions.

Identifying additional assumptions. While a single analyst may complete Figure 6.5, it is better to have groups of analysts work together because it is useful to bring more than one perspective to the table. Other analysts outside the core group also should be included in order to insert differing perspectives into the analytic process. These analysts ideally should differ in educational backgrounds, cultures, technical knowledge, or mindsets from the core group; but, it is wise to ensure the other analysts have applicable knowledge of the subject. The analyst(s) normally engage in a process best described as informed brainstorming.41,42 Chapter 8 provides details of additional techniques for informed brainstorming that may be used in identifying assumptions.

To proceed with their work, the analyst(s) should use the information collected on the situation (Chapter 5), results of the points of view analysis (this chapter), and any additional information provided by the core analytic team. As they complete the Four Ways of Seeing + Analyst and informed brainstorming, the team should consider:

- Why am I/are we confident the assumption is correctly identified?

- In what circumstances might key assumptions be overlooked?

- Could the assumption have applied in the past but is no longer applicable today?

- If the assumption turns out not to be applicable today, how much impact would including it have on the analysis?43

Categorizing assumptions. As the analysis of assumptions continues, the next step is to categorize the main sources of each, which is important because it provides insights the analyst can use in the belief analysis discussed below. U.S. critical theorist Stephen Brookfield offers three categories of assumptions— paradigmatic, prescriptive, and causal.44 These categories also may be used to classify key and supporting assumptions.

Brookfield highlights how assumptions operate as instinctive guides to behavior, which is something people seldom consider because assumptions reside deep within a person’s mental model. Assumptions influence how people think about the situation at hand. Brookfield offers they are difficult to evaluate as right or wrong, or valid or invalid, but should be considered as to whether they are more or less contextually appropriate for the situations they govern. Brookfield also boasts that identifying and categorizing assumptions is all that is needed in a critical-thinking analysis, although this book does not make that same leap of faith. He developed the following categories of assumptions:

Paradigmatic assumptions concern the deeply held assumptions that frame how a person views how the world works; in other words, the person’s “dominant personal ideology.” Paradigmatic assumptions go to the heart of a person’s points of view or personal belief system and include political, economic, religious, cultural, and social aspects of how the person views the way the world works. These assumptions usually spring from dominant ideologies (Appendix III). For example, the dominant ideologies of democracy and free-market capitalism are so pervasive in Western societies, their core assumptions often are never questioned in analyses. These core assumptions normally are accepted as the common-sense way of organizing and operating in the world. Paradigmatic assumptions often are hard to uncover, especially by analysts whose thinking is influenced by the same paradigmatic assumptions.

Prescriptive assumptions concern those that define the desirable ways a person thinks or acts. They are mainly normative because they define what “ought” or “should” be the desirable ways of thinking or acting and how the world “ought to” or “should” work. Prescriptive assumptions tend to flow from a person’s paradigmatic assumptions of how the world works. For example, prescriptive assumptions might define how a democracy should function or how resources ought to be allocated in a capitalist society. In addition to flowing from a person’s paradigmatic assumptions, prescriptive assumptions result from the structure of laws, regulations, policies, and rules telling people how they should act. There are many social rules (both formal and informal) that influence thinking and behavior and can be categorized as prescriptive assumptions.

Causal assumptions concern theoretical and evidence-based assumptions and beliefs about how different parts of the world work. Causal assumptions are generally statements or hypotheses about how one or more variables cause changes in another variable (Chapter 3). In social science, the basic form of causal assumptions entails propositions or hypotheses stating how human thinking, decisions, behaviors, or conditions in factor X, results in or cause a change in the human thinking, decisions, behaviors, or conditions in factor Y (i.e., the issue under study). In the physical sciences, causal conditions are much easier to assess as they have been established through repeated observation and analysis. In the social sciences, causal conditions are much more elusive because of the complexity of human behavior and the lack of research in many aspects of that behavior. Causal assumptions related to social science often are deemed suspect because of the small sample size of cases governing the proposed causal linkages. Just because one person or a small group of people think or behave in a certain way, does not mean their thinking or behavior can be generalized to the thinking or behavior of a larger group of people (part-to-whole logic fallacy). Further, just because someone behaves in a certain way in one situation, does not mean they will behave the same way in future situations (weak analogy logic fallacy). Causal assumptions also may offer statements of information (data, facts, evidence). Unfortunately, it is common to find causal assumptions offered in statements or arguments with no corresponding basis in correct information or logic. This highlights the importance of consistently checking the accuracy and validity of information and logic presented as causal assumptions.

Note: Some references categorize assumptions as either value assumptions or descriptive assumptions. Value assumptions are a combination of paradigmatic and prescriptive assumptions. Descriptive assumptions are causal in nature.

Most situations are governed by a mix of the three assumption categories—paradigmatic, prescriptive, and causal. Normally, approximately 80% of assumptions in a situation are causal in nature.45 Analysts may need to look deeper to uncover paradigmatic and prescriptive assumptions. This effort may cause additional revisions to the list of assumptions generated in the Four Ways of Seeing + Analyst and informed-brainstorming analyses.

Belief Analysis: An Introduction

Belief analysis provides a deeper investigation of assumptions and can reveal causal mechanisms that influence an agent’s decisions and behaviors. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary defines belief as “… a state or habit of the mind in which trust or confidence is placed in some person or thing … a tenet or body of tenets held by a group.”46 Beliefs are shaped by an agent’s knowledge base and information, points of view, and assumptions (see Figure 6.1). Investigating agents’ beliefs can help security analysts understand adversaries’ goals and motives, anticipate their strategies, and predict their responses to challenges and threats.

Techniques for assessing the role of beliefs in threat-based and overall decision-making situations are poorly developed. Social science has studied “belief systems” and “belief networks;” i.e., interrelated beliefs and their ideological foundations.47 Foreign policy and related psychology literature conceptualize beliefs as “attributions” that influence the factors agents view as causal.48 This literature fails to provide techniques to help analysts comprehend the structure of beliefs, grasp how beliefs affect agents’ understanding of threats, and predict agents’ responses to threats.

U.S. clinical psychologist Barnet Feingold has designed techniques that focus on these hitherto overlooked issues in belief analysis. Feingold’s conception, which he calls Critical Belief Analysis, claims to help analysts refine and deepen their understanding of how beliefs affect decisions and behaviors.49 This section provides a brief introduction to Critical Belief Analysis. An in-depth coverage of Critical Belief Analysis is beyond the scope of this book. Readers desiring additional information on Critical Belief Analysis should consult Feingold’s website at http://barneysplace.net/site/.

Security analysts can use Critical Belief Analysis to deepen their understanding of an agent’s beliefs, helping them more accurately accomplish the following:

- Explain and predict the agent’s decisions, behaviors, and policies.

- Estimate the probability that those decisions, behaviors, and policies will have the intended outcomes.

- Anticipate the agent’s reactions to failures of belief-inspired decisions, behaviors, and policies.

Security analysts also can use Critical Belief Analysis for self-examination. Critical Belief Analysis can sensitize security analysts to factors—such as their points of view, attitudes, and assumptions—that might bias their analyses. Doing so, helps analysts have confidence in their findings.

Critical belief analysis core concepts. Critical Belief Analysis focuses on the degree to which beliefs provide the guidance agents expect. As such, it encourages attention to: (1) the guidance agents assume that their beliefs provide, (2) the guidance those beliefs actually provide, and (3) the differences between agents’ expectations and reality. Agents will likely have no understanding of Critical Belief Analysis; therefore, when the analyst is addressing what the agent might assume, they must put themselves in the shoes of the agent and think similar to the agent. Information searches (Chapter 5) and points-of- view and assumption analyses (this chapter) are critical to the analyst’s ability to understand the agent’s thought processes.

Critical Belief Analysis encourages systematic attention to three commonly overlooked structural characteristics of beliefs that powerfully affect their utility: (1) the fundamental needs they allegedly satisfy, (2) the precision of their predictions, and (3) their viewpoints; that is, the nature of the issues they address and their relationships to other beliefs. In the absence of attention to these structural characteristics, agents are likely to view bias-distorted, inaccurate beliefs as factual. They are likely to overestimate the value of the guidance their beliefs provide and to deny the roles of their beliefs in fiascoes.

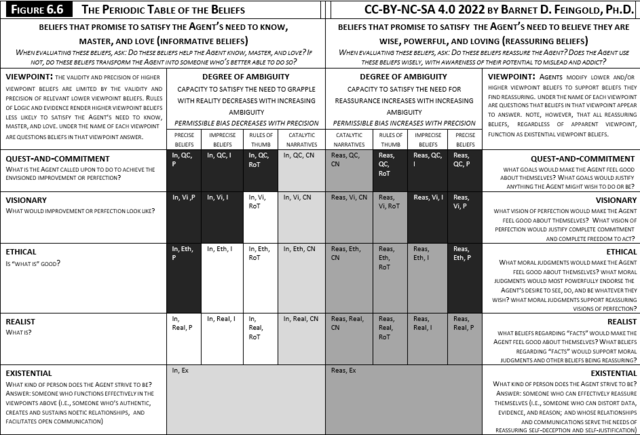

Figure 6.6, The Periodic Table of the Beliefs, summarizes the structural characteristics in Critical Belief Analysis. This table assists the reader in understanding the following discussion of the basics of Critical Belief Analysis. This table was designed to help analysts visualize the nature and limitations of the guidance beliefs provide, the relationships between beliefs, and the implications of disparities between agents’ and objective observers’ views of those beliefs. Analysts are encouraged to refer often to The Periodic Table of the Beliefs while conducting a Critical Belief Analysis.

Fundamental needs. Critical Belief Analysis maintains that agents look to beliefs to meet one or both of two fundamental needs. The first is the need for information to help them survive and prosper; information about how things are, what is likely to happen, and how to get things done. Beliefs that agents treat in ways that support satisfaction of these needs are called informative beliefs. The second is the need to feel comfortable and confident. Such feelings are the result of seeing oneself as wise, powerful, loving, connected, and valued, and seeing the world as safe and one’s position in it as secure. Such beliefs help agents cope with realities that might otherwise be overwhelming. Critical Belief Analysis refers to these as reassuring beliefs.

Agents reveal the fundamental need they assume their beliefs satisfy through their actions (statements, writings, behavior, etc.). If agents rely on their beliefs for guidance concerning consequential matters, they probably assume their beliefs to be informative. On the other hand, they may admit that they believe as they do even though the guidance of their beliefs is misleading or useless. In that case, they assume their beliefs to be reassuring. Of course, such self-awareness and integrity are rare. Agents are biased toward viewing their beliefs as informative; even those that—to objective observers—are transparently worthless or false. Reassuring beliefs can foster self-deception. Those beliefs that agents treat as reassuring offer vague, inaccurate, and generally questionable guidance. In addition, reassuring beliefs encourage agents to protect their beliefs with all available defenses, however invalid.

Determining whether a belief is informative or reassuring requires inquiry into the agent’s relationship with that belief. The belief is likely informative if that relationship embodies objectivity, open-mindedness, detachment, and the struggle against bias. The belief is likely reassuring if that relationship is characterized by attachment, bias, defensiveness, closed-mindedness, or rampant subjectivity. On occasion, it may be evident that agents relate to beliefs in ways that render them informative at some times and reassuring at others. Such ostensibly unitary beliefs should be analyzed as two distinct beliefs: one informative and one reassuring.

The precision/ambiguity of beliefs. The second characteristic of beliefs to which Critical Belief Analysis encourages attention is their precision/ambiguity. Critical Belief Analysis uses precision and ambiguity, like loudness and softness, to refer to different ways of describing the same phenomenon. A belief’s precision is the narrowness of its range of belief-consistent observations. The more precise a belief, the narrower the range of observations that support it and the broader the range of observations that challenge it. A belief’s ambiguity, on the other hand, is the breadth of that range. The more ambiguous a belief, the broader the range of observations that support it and the narrower the range of observations that challenge it.