The Intersectional Redneck:

Appalachian Identity Politics in Historical and Contemporary Perspective

Molly Clever and Katharine Lane Antolini

In the rolling hills and hollows of West Virginia, a sight may confound students of Civil War history: the Confederate battle flag waving proudly from front porches, attached as stickers to the back of trucks, and emblazoned on hats and t-shirts. While the Confederate battle flag is a common sight in many rural areas, particularly in the states that made up the former Confederacy, its presence in West Virginia highlights recent transformations in White identity politics and its associated symbols in the United States. West Virginia became a state on June 20, 1863, after a two-year struggle to break free from the state of Virginia and to secede from the Confederacy. Abolitionist politics played a central role in the founding of the state; a pathway toward the abolition of slavery was included in the state’s constitution, and the abolitionist slogan “Mountaineers are always free” was formally enshrined as the state’s motto.[1] Thus, the prominent display of Confederate symbols in the only state to secede from the Confederacy provides just one example of the many complexities of contemporary identity politics in modern Appalachia.

To disentangle these complexities, it is necessary to understand how Appalachian identity markers were constructed and evolved in the context of intersections between race, social class, and geography. The common stereotype of Appalachian hillbillies and rednecks consists of people who are poor, White, uneducated, and racist. However, this trope obscures a complicated intersectional history of race and class in Appalachia. For decades, Appalachian scholars have warned that such cultural caricatures problematically essentialize and universalize the residents of an entire geographic region.[2] Since the early 20th century, cultural outsiders have applied these slurs to denigrate Appalachians, building a taxonomy of the terms hillbilly and redneck that rests firmly on the foundations of Whiteness, unconcealed racism, and inherent violent tendencies. The intertwining of these characteristics has been so thorough that contemporary outsiders are perpetually perplexed when cultural insiders proudly embrace the monikers of hillbilly or redneck and their associated symbols. Such actions resonate as proof in the minds of national commentators of the region’s ingrained ignorance and further sustains its “Othering” in comparison to the rest of the country.

West Virginia serves as a case study for the evolution of these terms through the aftermath of the Civil War, the labor movement, and the Civil Rights movement. As the only state completely within Appalachia, national pundits and popular media often evoke West Virginia as representative of the entire region. Unfortunately, even Appalachian cultural insiders have ignored or dismissed aspects of the state’s history to cater to the current outsider depiction of its unquestionable and unapologetic Whiteness and political defense of racial privilege. To be sure, West Virginia illustrates evidence of interracial coalitions within the state’s history, complicating common stereotypes.

This history reveals a construction of Appalachian identity that has operated through two mutually constructive and highly contentious pathways: on the one hand, as a source of empowerment through cross-racial coalition building among workers, and on the other hand, as a source of racial division for the purposes of economic exploitation by elites. This complex weave of racial and social class politics has led to contemporary social movements for racial and economic justice in Appalachia.

Intersectionality in the Appalachian Context

Intersectionality is an analytical and theoretical framework for examining the interactions of various forms of privileged and oppressed identities. Intersectional theory emerged as an alternative to conventional additive models, which conceptualize identity-based oppressions in terms of discrete categories such as race, class, and gender. In contrast, intersectionality centers the interactions between these identities in analyses of identity-based oppressions. In its contemporary iteration, intersectionality gained prominence within critical race theory in the 1980s and 1990s. Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term to describe the ways in which anti-discrimination law rendered invisible problems facing Black women.[3] However, as many intersectional scholars have emphasized, Black feminist scholars and activists have been referencing the need to conceptualize the interactions between multiple identities in the fight for justice as early as the mid-19th century.[4]

Intersectional theory has most often been associated with Black feminism, both due to its origins within Black feminist critical race theory and because of its utility in describing the unique forms of marginalization and social invisibility that women and queer folks of color often encounter. Crenshaw’s formulation of intersectionality grew out of a need to render visible problems of employment discrimination faced by Black women, whose marginalization in the workplace couldn’t be readily classified as racial- or gender-based discrimination when the employer in question hired both women (who were White) and people of color (who were men). Crenshaw argued that conventional additive models were insufficient to explain the nature of the oppression experienced by Black women, and that intersectionality offered a way to “highlight the multiple avenues through which racial and gender oppression were experienced so that the problems would be easier to discuss and understand.”[5]

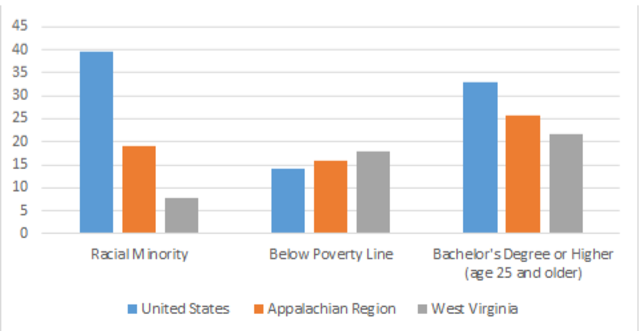

Similarly, applying an intersectional framework to Appalachian identity illuminates unique problems that occur within the interactions between race and social class. Compared to the rest of the United States, the Appalachian region is more White, more poor, and less educated. Within Appalachia, West Virginia specifically is even more disproportionately White, poor, and less educated (see Figure 1).[6] These demographic realities contribute to a cultural identity formation of Appalachians that is rooted in White poverty. According to bell hooks, this pattern creates a “politics of invisibility” that is manipulated by elites to maintain economic control through a “divide and conquer strategy”:

Better to have poor and working-class white folks believe white supremacy is still giving them a meaningful edge than to broadcast the reality that the poor of any race no longer have an edge in this society, or that downsizing daily drags previously economically sound white households into the ranks of the poor.[7]

Thus, the intersectional lens offered here by bell hooks uncovers an avenue for understanding the problems of economic marginalization in the Appalachian region by examining how poverty is structured within the broader economy. Appalachia’s disproportionately high levels of poverty in general, and West Virginia’s in particular, are rooted within the economic dynamics of extraction-based economies.

Figure 1. Race, poverty, and education indicators in the United States, Appalachia, and West Virginia by percentage of the population.

Extractive economies, such as those based on coal and timber, contribute to patterns of economic underdevelopment and political corruption. This phenomenon occurs through a process described by scholars as the resource curse hypothesis: because revenues from natural resource extraction go directly to corporate leaders and state coffers, there is a high potential for corruption and low incentive for building robust forms of democratic participation. This result occurs because elites have the opportunity to enrich themselves by skimming profits and have little incentive to bargain with or even learn about the needs and preferences of the local population.[8] Rather, elites in extractive economies are incentivized to suppress and politically marginalize their labor force in an effort to maintain high levels of profit. These profits are likewise extracted from the state–exported elsewhere for profit–rather than invested into local social and infrastructural development.

As natural-resource industries such as coal and timber declined in prominence through the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the number of people employed by (and therefore economically reliant upon) extractive industries has also declined. In West Virginia alone, the number of people employed by the coal industry dropped from just over 131,000 in 1948 to fewer than 14,000 in 2021.[9] In an attempt to maintain their power, political and corporate elites tied to the energy industry have engaged in identity construction strategies aimed at manufacturing a sense of cultural ideology that is inextricably tied to extractive industries and their interests, even as those interests operate in opposition to the social, environmental, and economic well-being of those in the poor and working classes.[10] For example, the “faux grassroots front group” Friends of Coal[11] was created by coal industry leaders in an effort to reduce the political effectiveness of labor and environmental advocacy groups through “the appropriation of West Virginia cultural icons and the infusion of coal-industry ideology into a variety of social arenas.”[12] This ideological reframing strategy fuses aspects of Appalachian identity–such as rural community traditions and personal grit–with coal-industry interests. Thus, local challenges to the coal industry–such as objecting to mountaintop removal or pressuring politicians to divert state resources into alternative forms of economic development–become redefined as a challenge to Appalachian identity itself.

This form of cultural manipulation likewise fuses with racial identity politics, as economic elites have an interest in constructing and perpetuating racial antagonisms within the poor and working classes. White supremacist ideologies become the cultural avenue through which divisions within the labor force can be produced and maintained. These divisions are further exacerbated by politicians, who use racial identity as a strategy of mobilizing political support. This approach included the “Southern Strategy,” a political tactic developed by the Republican Party in the 1960s and 1970s to gain an electoral advantage in Southern states by directly appealing to the anxieties and resentments of White residents in the post-Jim Crow era. By design, the Southern Strategy capitalized on the emerging dynamics of identity politics in the Civil Rights era with the goal of shifting the priorities of White working class voters away from economic interests (that were typically shared with those of the poor and working classes of all races) and toward a focus on White identity, often framed in terms of preserving the cultural integrity of traditional rural life. The Southern Strategy is therefore just one example of how elites politicize racial fault lines as part of a broader divide-and-conquer strategy meant to disempower the working class.[13]

This divide and conquer strategy was enacted upon West Virginia coal miners in the 20th century alongside evidence of an intersectional politics of resistance within the West Virginia Labor Movement. Legacies of this history in contemporary intersectional social movements for racial and economic justice occurred not only in West Virginia but also in the broader Appalachian region.

West Virginia Red Necks

Scholars date the popular usage of the term “redneck” to the late 19th century. It was a label meant not only to describe rural farmers and their “long red necks” sunburned from hours toiling in the field, but also a term specifically designed to exemplify rural Southern White residents united behind the ideology of White supremacy.[14] Throughout the 20th century, both rednecks and hillbillies were defined as “uncouth countrymen” resting on a violent racist nature that emerged easily when provoked. During periods of heated racial conflict, such as the struggle to integrate Southern schools in the 1950s and 1960s, media accounts resorted to stereotypical redneck and hillbilly name-calling when describing the angry White working-class crowds shouting at Black students attempting to enter all-White schools. By the mid-20th century, according to historian Nancy Isenberg, “redneck” had become “synonymous with an almost insane bigotry.”[15]

Terms associated with groups can morph over time. For West Virginians raised on the history of the state’s coal industry, the term “redneck” is not one that invokes insane racial bigotries but one that represents an encompassing class consciousness strong enough to diminish racial and ethnic strife. In the early fall of 1921, striking miners from the state’s southern coal counties led the largest armed insurrection in the nation’s history since the Civil War, known as the Battle of Blair Mountain. An estimated 15,000 to 20,000 men joined the armed march that led to Blair Mountain.[16] Within its ranks, White, Black, and immigrant miners, under the leadership of the United Mine Workers of America, knotted red bandanas around their necks as a symbol of their united goal to overthrow the oppressive policies and practices of the region’s coal companies. Upon witnessing the bandana-clad union miners as they marched past, on-scene reporters referenced the men as “red necks” in news stories that drew a nationwide audience.[17] During the early 20th century, therefore, the term “redneck” held multiple and conflicting meanings within the context of the unionization movement in West Virginia’s southern coal fields. Although the usage and meaning of the word varied between coal operators, hired mine guards, and the coal miners themselves in this period, what remained conspicuously absent from the “redneck” label was its traditional connotation of White supremacy.

The history of the coal industry in Appalachia challenges the image of the region’s severe isolation and staunch homogeneity that supposedly differentiated it from the rest of the country. This perceived isolation of the region and its White mountaineer population has fed the racial narrative behind the redneck and hillbilly stereotype for centuries, prompting historian John C. Inscoe to speculate that “no other aspect of the Appalachian character has been as prone to as much myth, stereotype, contractions, and confusion as has the matter of race relations and racial attitudes among mountaineers.”[18] Early travel writers once attributed the region’s apparent moral and economic aversion to slavery, for instance, as a form of racial naivety born from the Southern mountaineer’s lack of interaction with Black Americans. But by the late 19th century, that same muted interracial exposure was reasoned to be the root of the redneck’s violent racist nature.[19] A closer look into the region’s coal industry further complicates the discussion of racial attitudes and relationships. Scholars paint Appalachian coal towns at the turn of the 20th century as a “bewildering array of peoples and cultures.”[20] Such a depiction stands in stark contrast to the traditional image of an isolated and solely White mountain populace.

In reality, bituminous coal was a resource too massive for native White mountaineers to dig alone. The Appalachian region contained the nation’s largest supply of fossil fuels, over fifty million acres, thus coal companies depended on the labor of Southern Black residents as well as immigrants to help extract the vital resource. The migration of diverse groups into the Appalachian coalfields began in earnest. This mass addition to the labor force, accompanied by access to national markets through newly constructed railroad lines, enabled the region’s coal production to triple by 1900. By 1930, 80 percent of the nation’s total coal production came from the Appalachian coalfields.[21] Of all those coalfields, however, the southern fields of West Virginia held the strongest attractions for these vital new workers, offering more economic, social, and political freedom than the neighboring coal producing states.

The primary goal of West Virginian coal operators was to build productive and profitable mines. Such productivity depended upon a well-regulated labor force. The higher transportation costs of hauling coal from remote hollows to outside markets meant operators needed to keep labor costs at a minimum. Paying the higher union wages earned by miners in the coalfields of Northern states, for example, risked West Virginia’s ability to compete.[22] Low miners’ wages were essential to the industry’s profit margins; pick miners in the state’s southern coal counties earned 38.5 cents per “long ton” (2,240 pounds) in 1912 while miners’ wages in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania reached as high as $1.58 per “short ton” (2,000 pounds).[23] Thus, sustaining a productive, compliant, and non-union labor force was a high-stakes investment for coal operators.

The policy of judicious mixture governed the industry’s labor recruiting. Coal operators believed a relative balance of White, Black, and European immigrant residents would address their need for a stable and especially a non-union workforce. Native mountaineers, according to operators, were not the most reliable and disciplined of miners, prone to absenteeism and lacking deference to company authority. Operators hoped to mitigate the issues with White miners by recruiting Southern Black residents and European immigrants in larger numbers. The policy of judicious mixture was based on two main assumptions about the Appalachian labor force: First, that Black and immigrant laborers would work harder and be more obedient than White miners; second, that White miners would hold racist and nativist resentments against their Black and immigrant counterparts and that these resentments would prevent interracial solidarity and help squelch union sentiment.[24] In other words, the policy of judicious mixture was designed to draw on, reify, and amplify existing racial and ethnic fault lines. By 1920, the judicious mixture of the state’s mining force approximated 25 percent Black, 20 percent southern European immigrant and 55 percent native White.[25]

Despite the lower wages common to the Southern coalfields, West Virginia’s mines offered steadier employment and a possibility of a higher total annual income in comparison to higher paying Northern mines.[26] The promise of steady work lured Black miners from the Southern states. Yet Black families migrated to the state for opportunities beyond just economic gain; they sought additional opportunities nonexistent in other regions at the turn of the 20th century. In the South, Black residents lived under oppressive Jim Crow laws that implemented rigid social segregation, denied Black men political rights, and sanctioned the physical brutality of lynching as a weapon of intimidation and control. West Virginia, in contrast, shone as a beacon within the Appalachian Mountains. Labor recruiters promised equal wages, the right to vote, and a quality of education denied to Black residents in the South and other Appalachian states. Such opportunities served the coal industry’s interests as well; they attracted new miners during periods of increased labor shortages, and, according to West Virginia coal operators, created a more productive and stable workforce. To suggest that Black miners were never victims of racial discrimination or violence would be a gross exaggeration, of course. Nonetheless, race relations proved less contentious in the company towns of the Mountain State than in other coal-producing states. By 1920, nearly 70 percent of the Black population living in Appalachia called the hills and hollows of West Virginia home.[27]

In addition to the South, coal companies sent labor recruiters to the Eastern port cities of Philadelphia, New York, and beyond in search of European immigrant workers willing to work in the mines. In 1864, the West Virginia legislature appointed its first immigration commissioner, Joseph H. Diss Debar, a Swiss immigrant himself, and empowered him to promote the state’s merits to Americans and foreigners alike.[28] Diss Debar published The West Virginia Hand-Book and Immigrant’s Guide in 1870 to better assist his efforts. He insisted the guide offered “unvarnished facts and figures” based on his own personal observations and professional experiences as a twenty-five-year resident of the state. “It is hoped that its freedom from all romance and exaggeration may secure for it the attention and confidence of that class of honest and enterprising workers in both hemispheres,” stressed Diss Debar in the preface, “whom we are most anxious to welcome as permanent settlers to our infant state.”[29] The guide provided an overall sketch of the state from its historical origins and state constitution to a meteorological chart detailing the average weather on any given day of the year. And, of course, the guide detailed the state’s diverse industries including a portrait of its mineral resources. Within the state, Diss Debar explained, laid the largest and best coal seams of the Allegheny Mountains–all “naturally opened to development.”[30] West Virginia sent such guides throughout Europe in the late 19th century to promote immigration, followed by labor agents paid by the coal industry to make direct appeals in the early 20th century.[31] Like Southern Black residents drawn to coal towns before them, European immigrants were also victims of nativist fears in West Virginia. Historical studies document clear evidence of economic and physical abuse inflicted upon immigrant miners by both the coal companies and by White and Black miners. Nevertheless, immigrants representing all the nations of Europe and numbering 32,000 people, lived and worked in the state by World War I.[32]

Yet the policy of judicious mixture, designed to cultivate racist and nativist fears and generate an atmosphere of cultural suspicion and economic competition, backfired on the state’s coal operators in the early 1900s. The experiences of life working deep underground forged bonds between men regardless of race and ethnicity. The majority of the nation’s coal was mined by hand until 1915. Even after the adoption of machinery to cut into the coal seams, miners continued to hand-load coal cars until the 1940s.[33] In West Virginia, all White, Black, and immigrant miners worked side by side, earned the same pay per ton of coal they dug and loaded, and emerged from the mines each evening blackened by the same coal dust. They also faced the same dangers. A miner in West Virginia was more likely to be killed by a methane gas explosion or a roof collapse than any miner employed in the United States or Europe. For example, the 1907 Monongah mine explosion in central West Virginia killed over 350 men and boys, and it ranks among the worst mining disasters in the nation’s history. Indeed, miners in the Southern coalfields experienced a higher proportional death rate than American soldiers serving in World War I. Faced with such odds, West Virginian miners reportedly adhered to a “sacred code” that bound them to risk their own lives after a disaster to rescue trapped miners or recover every dead body. Coal operators typically blamed the gruesome injury and death rates on an “act of God'' or miner carelessness to hide the company’s failure to adhere to the few mining safety codes that existed in the early 20th century.[34] Miners quickly learned that coal companies valued profit over their lives and the welfare of their families. Such a grim revelation bred collaboration more than competition between the men.

Above ground, the design of mining towns further lessened the total effectiveness of judicious mixture. Company towns were born out of necessity in the 1880s when the industry first sought to access coal seams deep in the remote hollows. In the absence of any nearby towns, companies built their own to provide the means of operations that included the need to house, supply, educate, and even entertain its miners and their families. The power that coal companies wielded in the towns they constructed throughout Appalachia is legendary—but no more so than in West Virginia. The majority of West Virginia miners, an estimated 94 percent, lived in “company towns,” and West Virginia held the highest percentage of any coal-producing state with the next closest state being Illinois at 53 percent. [35]

The coal company owned the entire town from the top of the coal tipple to the deepest chamber of the mine. The houses where the miners lived, the store in which they shopped, the church where they worshiped, and the school where they sent their children each week were all company property. Such an arrangement granted coal operators the power to ensure both economic and physical control over the miners. Economically, operators paid miners in company-printed money called “scrip” that was only redeemable in full at the company store. Contemporary investigations of coal industry practices discovered that company stores hiked prices as much as three times higher than the cost of food and clothing in stores in local towns. What losses a mine accrued during a slump in the coal market, it easily recuperated from profits made at the company store. State law also defined the relationship between coal company and miner differently in regard to housing. Miners did not have the rights and legal protections awarded the traditional renter. Instead, courts defined the relationship as one of “master and servant,” which meant they could evict a miner and his family from company housing for any reason and without warning.[36]

Despite the policy of judicious mixture, however, company towns were often not governed by rigid racial segregation. Only the integration of schools and interracial marriage were fully banned under West Virginia law. Thus, integrated (or at least semi-integrated) company towns were more the norm than the exception according to historians. Some companies chose to segregate housing; sections of towns nicknamed “n***er hollow,” “little Italy,” or “hunktown” to identify the race and ethnicity of its residents testifies to that fact. Yet even when such segregation existed, the typically small size of mining towns meant Black and immigrant families remained in close vicinity to White families—perhaps no more than a few hundred yards “up the hollow.” Moreover, all miners lived in similar quality of housing and paid the same monthly rent based on the size of the house and not the race or ethnicity of its occupants. Despite the homogeneity of housing, homes in the majority of company towns were, unfortunately, equally awful. In 1925, the U.S. Coal Commission identified the living conditions in the mining towns of central Appalachia as the worst in the country.[37]

West Virginian miners were ultimately drawn together by their lived experiences while working and socializing along with their shared sense of powerlessness strong enough to temporarily silence racist and nativist fears. Because coal towns were unincorporated entities, county and state officials considered them the private property of the company and respected the operators’ right to oversee their own affairs. It was common for coal companies to pay local law enforcement to either ignore the company’s management of its labor force or assist directly with that management. The most notorious example of such a relationship was with Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin. Coal operators paid Chafin $2,725 each month to protect their interests, which primarily meant preventing “union agitators” from entering the county. The Logan County Coal Operators’ Association paid over $60,000 for Chafin’s and his deputies’ services in 1921. In the absence of local law enforcement, companies hired private guards from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency in Bluefield, West Virginia, to enforce order within company towns. Historians have compared the mine guard system employed by company towns to living under a police state.[38]

Historian David Corbin insists the combined hardships of work and life within the company towns laid the foundation for a “class over caste” solidarity among miners. “The nature of the company town focused the workers’ discontent, not on each other or on a racial or ethnic group,” explains Corbin, “but upon the employer—the coal operator—enabling the miners to develop that sense of group consciousness necessary for class feeling and behavior.”[39] This class consciousness drove the unionization movement. The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) initiated its first campaign to unionize all West Virginia coalfields in 1897. Although able to organize the state’s northern fields, the southern fields remained pugnaciously closed from UMWA efforts thanks to men like Sheriff Chafin in Logan County and the Baldwin-Felts guards in Mingo County. This period of brutal fighting over unionization is collectively known as the West Virginia Mine Wars (1912-1921). The decade included a series of union and wildcat strikes (including Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike, 1912-1913) and deadly clashes between miners and mine guards (such as Battle of Matewan and the Battle of the Tug in 1920). The Mine Wars ended with the armed Miners’ March on Logan in August-September 1921. Thousands of miners initiated a march to Mingo County to rescue imprisoned miners and their families suffering under a declaration of martial law. Sheriff Don Chafin and his men stopped them in Logan County at Blair Mountain. The five-day battle, along a 12-mile front, ended only after the deployment of federal troops and the willing surrender of the miners on September 4, 1921.[40]

Miners, coal operators, and mine guards disputed both the right to unionize and the meaning of the term “redneck” during the Mine Wars. The connection between the symbol of the red bandana and unionization in West Virginia history dates back to the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. At that time, B & O Railroad line workers in Martinsburg donned red bandanas as they joined the rail strike in protest of successive wage cuts. It was during the Paint Creek and Cabin Creek Strike, 1912-1913, however, when the word “red neck” first appeared in print in a labor context and in reference to union miners. Coal operators and mine guards employed the word as a derogatory epithet to identify miners as both union members and poor White mountaineers.[41] However, not all the union men who defied coal company authority were poor White mountaineers. The strength of the UMWA movement relied on interracial collaboration during the Mine Wars. It was the union’s mission to organize West Virginia miners regardless of “race, creed, or nationality,” and Black and immigrant miners bravely joined its ranks in spite of the higher risk of reprisals faced by non-White miners and their families for that union support.[42]

The Miners’ March and the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921 was a dramatic demonstration of working class consciousness and solidarity. White, Black, and immigrant miners united against a common foe to form a “Red Neck Army.” In this context, the UMWA appropriated the “redneck” label to represent a multi-racial and ethnic unity, symbolically tied together by the wearing of a red bandana. A mundane item routinely worn underground by miners to protect themselves from the hazard of coal dust had begun to serve as an emblem of group identity in their fight to protect themselves from the abuses of coal operators and mine guards.[43] Between 2,000 and 5,000 Black miners joined the “Red Neck Army,” and 400 of them were briefly imprisoned afterwards—twice as many as White miners.[44] Upon later reflection of the march, a White miner described its interracial design as a “darn solid mass of different colors and tribes, blended together, woven, bound, interlocked, tongued and grooved and glued together in one body.”[45] The miners’ actions as they marched through the town of Sharples in Logan County exemplifies the sentiment behind the miner’s recollection. The company mess hall in Sharples was segregated by race and class. The marchers demanded that the cooks prepare food for all the miners to be served together in the room reserved for management before they continued on their way.[46]

The miners’ self-identification as “rednecks” continued throughout the 1930s. Labor historians trace the term’s adoption by organized miners in other Appalachian states in the early 20th century.[47] By World War II, however, the popular association of the term to mean “proud union man” or to represent class consciousness and multiracial solidarity faded. The positive connotations of the red bandana and “redneck” label waned within West Virginia along with the memory of the Mine Wars. Immediately after the miners surrendered at Blair Mountain, coal companies joined with state officials to effectively expunge the Mine Wars from West Virginia history. They had the power to control the narrative in the local and national media and effortlessly characterized decades of labor unrest in the West Virginia coalfields as a product of socialist propaganda concocted by outside union agitators. When the state required West Virginia history to be taught in the school systems by the 1930s, detailed accounts of labor unrest in any of the state’s industries were excluded from the approved curriculum. That was just the first step in rewriting the state’s labor history for both local and national consumption.[48]

Fortunately, the legacy of the Mine Wars, the emblem of the red bandana, and the reclaiming of the redneck epithet to represent “class over caste” was never completely erased from the memory of later generations of West Virginians. “This is the kind of history,” notes Mine Wars historian Charles Keeney, “that turns stereotypes on their heads and redefines identity.”[49]

Contemporary Appalachian Intersectional Movements

The legacy of these stereotype-defying historical events is evident in contemporary intersectional social movements for racial and economic justice. In 2017, nearly a century after the Battle of Blair Mountain, teachers donned the same red bandana during the West Virginia teachers’ strike and embraced the historical “redneck” identity as a person who unites across class and race in defense of economic justice. In February 2017, 20,000 state teachers, school personnel, and bus drivers representing all 55 counties walked away from their jobs. The decision to shut down the state’s school systems for thirteen days was both a bold and heart-wrenching choice for the strikers. Nevertheless, they understood how fighting in defense of their own quality of life and value as state employees also meant fighting for a quality of education that all of their students deserved.[50]

It seemed inevitable that teachers from the southern counties emerged as leaders of the strike; they drew upon a rich legacy of parents and grandparents who bravely stood up against the authority of coal companies in defense of their own dignity as workers. In their published recollections of the strike, teachers from Mingo County especially recognized the weight of history on their shoulders. “Although there’s an understanding that striking is illegal, people in the south fear more serious repercussions: disappointing our ancestors,” wrote West Virginia English teacher Katie Endicott. She believed the willingness to stand in a picket line was instinctive to her; it was mapped on her DNA.[51] For thirteen days in 2017, the teachers and their allies formed a modern “Red Neck Army,” as they stormed the state capitol in Charleston fighting for the rights of all who worked within the state’s public school system. “The past was there, in the sharp and cold mornings, when the teachers of the coalfields rose to take their place in a long tradition,” describes historian Elizabeth Catte. “The descendants of the Mine Wars have inherited the Mind Wars. March on.”[52]

The West Virginia teachers’ strike is one example of using redneck identity in an intersectional justice frame. Other movements across Appalachia are drawing on similar constructions of identity to mobilize toward racial and economic justice, such as the Poor People’s Campaign (PPC), which emerged directly from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in the late 1960s. King had long pointed to economic inequality as a key component in the fight for racial justice that characterized the Civil Rights movement. However, by 1967 he had become increasingly frustrated that the 1964 Civil Rights Act had done little to alleviate the suffering of the poorest Americans in a period in which the United States was experiencing historically high levels of economic growth and global power. King rejected the identity politics of the Black Power movement, arguing:

The unfortunate thing about [the slogan] Black Power is that it gives priority to race precisely at a time when the impact of automation and other forces have made the economic question fundamental for blacks and whites alike. In this context, a slogan of “Power for Poor People” would be much more appropriate.[53]

The aim of the PPC was to organize a multiracial coalition of the poor and oppressed to march on Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1968 and demand that the federal government take immediate steps to alleviate the deplorable conditions of poverty through guaranteed jobs, income, and industrial development in rural areas. The movement organized Mule Trains–tarp-covered wagons pulled by mules–to transport groups of rural poor to Washington, D.C., where they set up an encampment on the national mall known as “Resurrection City.”

The high concentrations of poverty in the rural South in general, and Appalachia in particular, made the region a central focus of the PPC. Indeed, forming interracial coalitions and organizing in Appalachia were central to the Civil Rights movement throughout its history. Both Rosa Parks and King trained at the famous Highlander Folk School in Tennessee in the 1950s, one of the few places in the Jim Crow South where interracial meetings occurred (albeit illegally). In a speech at the Highlander Folk School in 1957, King emphasized the relationship between racial and economic justice:

Organized labor has proved to be one of the most powerful forces in removing the blight of segregation and discrimination from our nation. Labor leaders wisely realize that the forces that are anti-Negro are usually anti-labor, and vice versa. And so organized labor is one of the Negro's strongest allies in the struggle for freedom.[54]

Appalachian leaders were central to PPC organizing. Highlander Folk School founder Myles Horton became a lead organizer of Mule Train and education tents that were part of Resurrection City.

While in Memphis to help striking sanitation workers obtain better wages and working conditions, King was tragically assassinated just weeks before the PPC march was planned to begin. Nevertheless, approximately 50,000 poor and working-class Americans took the Mule Trains to Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1968 with thousands camping in Resurrection City for nearly six weeks. However, the PPC dissolved quickly in the aftermath of King’s death. Public attention had shifted toward the collective grief and violence that characterized the summer of 1968, and by late June, Washington, D.C., police had forcibly expelled the residents of Resurrection City.[55] According to historian Robert Chase, the collapse of the PPC is best explained by the challenges to power that lies behind interracial coalitions for economic justice:

Ultimately, the PPC failed because the traditional constituency of the Civil Rights movement–the white, middle-class, liberals–was repulsed by the goals of the campaign itself. Bringing the poor together as a racial amalgamation of similar interests and goals heightened the issue of class in America and, consequently, Americans came to view the Civil Rights movement as an instrument questioning the legitimacy of America’s economic system and its capitalistic “way of life.”[56]

In subsequent years, public perceptions of King’s legacy became tightly tied to his fight for racial justice, with little attention paid to his “last crusade” to shift the balance of power in America toward the poor and working classes. Fifty years later in the spring of 2018, however, a revival of the PPC, led by Rev. Dr. William Barber II, once again marched on Washington in an effort to draw attention to the suffering of the poor and the need to focus on the interactions between racism and poverty. Central to the new PPC’s core principles is the premise that “[p]overty and economic inequality cannot be understood apart from a society built on White supremacy.”[57]

The role of global capitalism as a barrier to economic and racial justice is likewise a focus of many recent and current social justice movements. In the 1960s and 1970s, a group from the Students for a Democratic Society chapter at Marshall University created the Appalachian Movement Press. The premise behind the activist press movement was to challenge the capitalist production of cultural products. By owning their own means of production, activist presses could construct cultural narratives by and for marginalized people. The Appalachian Movement Press operated under the internal colony theory, an extension of the resource curse hypothesis, which posits that people living in regions with extraction-based economies are systematically exploited and marginalized by their own governments for the economic benefit of those living outside the region.[58]

This approach of seizing control of the construction of Appalachian identity away from outsiders is further evident in the Affrilachian artist movement. In the 1990s, Kentucky-born poet Frank X Walker coined the term Affrilachian to counter the stereotypes of “Appalachian” as a homogeneously White identity. The term spread to encompass a wide range of poets, visual artists, and musicians whose work focuses on intersectional Appalachian identity. According to Walker, “part of how we define ourselves [as Affrilachian artists] is grounded in being a champion of working class and poor people, and people who live at the margins. The Affrilachian poets have a motto, or an aesthetic, that says, ‘We make the invisible, visible,’ or try to give voice to the muted.”[59] Today, the Affrilachian movement has created a vibrant and diverse community of artists across the region whose work centers on struggles for social justice. Taken together, these movements exemplify the long, complex, and contemporarily vibrant nature of an intersectional Appalachian identity.

Lessons from Intersectional Rednecks

Indeed, the image of the Confederate battle flag waving through the hills and hollows of West Virginia is an apparent contradiction to its origins as the only state to secede from the Confederacy. Through the complex and stereotype-defying history traced in these pages, this contradiction serves a purpose: Rather than demonstrating allegiance to a particular political cause, the Confederate battle flag becomes a symbolic marker of identity among those whose experiences lie at the intersection of Whiteness, economic marginalization, and rural location. It is a symbol of the racial divide that is produced and maintained by political and business elites for the purposes of economic exploitation.

As bell hooks argues, however, these racial divisions among poor and working-class Appalachians are not absolute, and they are not without challenge.[60] Recent transformations in the global economy and communication technologies have meant that “today’s culture is one where the White and Black working class and poor have more to say to each other, [and] there is a context of solidarity that did not exist in the past.” She goes on to argue that class unity has the potential to supersede racial divisions only if class-based solidarity is “rooted in a politics of resistance that is fundamentally anti-racist, one that recognizes that the experiences of underprivileged White folks are as important as those of people of color.”[61] The intersectional rednecks of West Virginia provide one context for understanding how this politics of resistance constructs an Appalachian identity that is rooted in antiracism and economic justice.

Bibliography

Bailey, Kenneth R. “Strange Tongues: West Virginia and Immigrant Labor to 1920.” In Transnational West Virginia: Ethnic Communities and Economic Change, 1840-1940. Edited by Ken Fones-Wolfe and Ronald L. Lewis, 243-60. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2002.

Bell, Shannon Elizabeth, and Richard York. “Community Economic Identity: The Coal Industry and Ideology Construction in West Virginia.” Rural Sociology 75 (2010): 111-43.

Catte, Elizabeth. What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia. Cleveland: Belt Publisher, 2018.

Catte, Elizabeth, Emily Hilliard, and Jessica Salfia, eds. 55 Strong: Inside the West Virginia Teachers’ Strike. Cleveland: Belt Publisher, 2018.

Chase, Robert, “Class Resurrection: The Poor People’s Campaign of 1968 and Resurrection City.” Essays in History 40 (1998): 26-40.

“The Coal Town System.” American Experience: The Mine Wars, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/minewars-coalcamps/

Corbin, David A. Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880-1992. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2015.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (1991): 1241-299.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Why Intersectionality Can’t Wait.” Washington Post, September 24, 2015.

Diss Debar, Joseph. The West Virginia Hand-Book and Immigrant Guide: A Sketch of the State of West Virginia. Parkersburg: Gibbens Bros, 1870.

Eller, Ronald D. Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: Industrialization of the Appalachian South, 1880-1930. Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1982.

Green, James. The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia’s Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2015.

Goldberg, Ellis, Erik Wibbels, and Eric Mvukiyehe. “Lessons from Strange Cases: Democracy, Development, and the Resource Curse in the U.S. States.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (2008): 477-514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414007313123

Harkins, Anthony. Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon. Oxford: University Press, 2004.

Hawkins, Anthony, and Meredith McCarroll, eds. Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2019.

hooks, bell. Where We Stand: Class Matters. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Huber, Patrick. “Red Necks and Red Bandanas: Appalachian Coal Miners and the Coloring of Union Identity, 1912-1936.” Western Folklore 65 (2006): 195-210.

Inscoe, John C. “Race and Racism in Nineteenth-Century Southern Appalachia: Myths, Realities, and Ambiguities.” In Appalachia in the Making: The Mountain South in the Nineteenth Century. Edited by Mary Beth Pudup, Dwight B. Billings, and Atlina L. Waller, 103-31. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Isenberg, Nancy. White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America. New York: Viking, 2016.

Inwood, Joshua F. J. “Neoliberal Racism: The ‘Southern Strategy’ and the Expanding Geographies of White Supremacy.” Social & Cultural Geography 16 (2015): 407-23.

Keeney, Charles B. The Road to Blair Mountain: Saving a Mine Wars Battlefield from King Coal. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2021.

Keeney, Charles B. “The Mind Guard System: Mine Wars and the Politics of Memory in West Virginia.” West Virginia History: A Journal of Regional Studies 12 (2018): 47-70.

King, Martin Luther Jr. “‘Look to the Future,’ Address Delivered at Highlander Folk School’s Twenty-fifth Anniversary Meeting.” In The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Volume IV: Symbol of the Movement, January 1957-December 1958. Edited by Clayborne Carson, Susan Carson, Adrienne Clay, Virginia Shadron, and Kieran Taylor. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Educational Institute, Stanford University.

Laurent, Sylvia. King and the Other America: The Poor People’s Campaign and the Quest for Economic Equality. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.

Lewis, Ronald L. “Beyond Isolation and Homogeneity: Diversity and the History of Appalachia.” In Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes. Edited by Dwight B. Billings, Gurney Norman, and Katherine Ledford, 21-46. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

Lewis, Ronald L. Black Coal Miners in America: Race, Class, and Community Conflict 1780-1980. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1987.

Platt, Pam. “Frank X Walker: ‘Organize, Be Informed, Resist! And Vote with Your Wallet.’” Leo Weekly, February 1, 2017. www.leoweekly.com

Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. “Our Principles.” https://www.poorpeoplescampaign.org/

Pollard, Kelvin, and Linda A. Jacobsen Pollard. “The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview from the 2014-2018 American Community Survey.” Population Reference Bureau, June 2020.

Romero, Mary. Introducing Intersectionality. Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2018.

Slifer, Shaun. So Much to Be Angry About: Appalachian Movement Press and Radical DIY Publishing, 1969-1979. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2021.

Trotter, Joe William Jr. “Black Migration to Southern West Virginia.” In Transnational West Virginia: Ethnic Communities and Economic Change, 1840-1940. Edited by Ken Fones-Wolfe and Ronald L. Lewis, 137-60. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2002.

Trotter, Joe William Jr. Coal, Class and Color: Blacks in Southern West Virginia, 1915-1932. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

West Virginia Office of Miners’ Health and Safety, “Summary of Coal Production/Employees/Accidents, 2021.” https://minesafety.wv.gov/summary-production-employees-accidents-summary/

Woods, Michael E. “Mountaineers Becoming Free: Emancipation and Statehood in West Virginia.” West Virginia Journal 9 (2015): 35-71.

Zimring, David R. “‘Secession in Favor of the Constitution’: How West Virginia Justified Separate Statehood during the Civil War.” West Virginia History 3 (2009): 23-51.

[1] This process was not without controversy, however. See Woods, “Mountaineers Becoming Free,” 35-71; Zimring, “Secession in Favor of the Constitution,” 23-51.

[2] For the most recent discussion see Catte, What You Are Getting Wrong about Appalachia; Hawkins, Appalachian Reckoning.

[3] Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins,” 1241-299.

[4] Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I A Woman” speech is often pointed to as one of the earliest articulations of an intersectional framework. Also see Crenshaw, “Why Intersectionality Can't Wait”; Romero, Introducing Intersectionality.

[5] Crenshaw, “Why Intersectionality Can’t Wait.”

[6] Pollard, “The Appalachian Region.”

[7] hooks, Where We Stand: Class Matters, 117.

[8] Goldberg, “Lessons from Strange Cases,” 477-514.

[9] Bell, “Community Economic Identity," 111-43.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, 111.

[12] Ibid, 139

[13] Inwood, “Neoliberal Racism,” 407-23.

[14] Harkins, Hillbilly; Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas”; Isenberg, White Trash.

[15] Isenberg, White Trash, 265, 247-52, 255.

[16] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion.

[17] Green, The Devil is Here in These Hills; Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” 203-04; Keeney, The Road to Blair Mountain, 48-49.

[18] Inscoe, “Race and Racism,” 103-31.

[19] Ibid, 103-31.

[20] Lewis, Black Coal Miners in America, 122.

[21] Lewis, “Beyond Isolation and Homogeneity,” 21-46.

[22] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 108.

[23] Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 178.

[24] Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 167-75; Lewis, Black Coal Miners in America, 134-35; Lewis, “Beyond Isolation and Homogeneity,” 37-38.

[25] Trotter Jr., “Black Migration to Southern West Virginia,” 137-60; Lewis, Black Coal Miners in America, 134-36.

[26] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 31.

[27] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 62-63; Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 169-70; Lewis, Black Coal Miners in America, 141-56; Trotter Jr., Coal, Class, and Color, 102-22.

[28] Bailey, “Strange Tongues,” 243.

[29] Diss Debar, The West Virginia Hand-Book and Immigrant Guide, v.

[30] Ibid, 121.

[31] Bailey, “Strange Tongues,” 250-58; Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 168, 173.

[32] Bailey, “Strange Tongues,” 250-58; Green, The Devil is Here in These Hills, 173-74.; Lewis, “Beyond Isolation and Homogeneity,” 35-38.

[33] Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 175-76.

[34] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 10; Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 179-82; Green, The Devil is Here in These Hills, 73-76.

[35] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 8.

[36] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 8-10; Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 182-98; Green, The Devil is Here in These Hills, 20-31.

[37] For a detailed discussion of the design and conditions of company towns see Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 61-101; Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 182-98; Green, The Devil is Here in These Hills, 20-30; Lewis, Black Coal Miners in America, 146-56; Trotter Jr., Coal, Class, and Color, 125-44.

[38] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 115; Eller, Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers, 193-94; Green, 22-23, 49, 182-84; Keeney, The Road to Blair Mountain, 2-3; Lewis, Black Coal Miners in America, 157-60.

[39] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 61.

[40] Keeney, The Road to Blair Mountain, 2-3.

[41] Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” 196-97; Keeney, The Road to Blair Mountain, 47-48.

[42] Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” 198-99; Trotter Jr., Coal, Class, and Color, 113.

[43] Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” 204.

[44] Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” 204; Lewis, Black Miners in America, 157, 163; Trotter, Coal, Class and Color, 112.

[45] Trotter, Coal, Class and Color, 113.

[46] Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion, 222; Keeney, The Road to Blair Mountain, 68.

[47] Huber, “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” 196, 207.

[48] Keeney, “The Mind Guard System,” 47-70.

[49] Keeney, The Road to Blair Mountain, 68.

[50] The strikers were seeking a 5 percent pay raise and restoration of health care benefits. Catte et al., 55 Strong, 6-15.

[51] Ibid, 24.

[52] Ibid, 112.

[53] Laurent, King and the Other America, 5.

[54] King, “Look to the Future.”

[55] Laurent, King and the Other America, 4.

[56] Chase, “Class Resurrection.”

[57] Poor People's Campaign, “Our Principles.”

[58] Silfer, So Much to be Angry About.

[59] Platt, “Frank X Walker.”

[60] hooks, Where We Stand: Class Matters, 117.

[61] Ibid, 117.