Ravaged Land and Polarized People:

Community Response to Strip Mining in Eastern Kentucky, 1946-1972

Jacob Johnson

Several key events in the historical evolution of strip mining in Appalachia construct a history of the common people of Appalachia, their response to the emergence of strip mining, and the ways in which they have lived in and coped with these ruined lands. Therefore, a history of the people encompasses not only the powerful grassroots opposition against strip mining but also the communal divides created by the economic and coercive influence of coal mines and coal interests, which have led to the rise of an equally powerful grassroots support in favor of practices that have continued to drastically change the landscape.

Strip mining emerged as a method of coal extraction in the 1940s and has since been a contentious subject for the region due to the destructive nature of the practice. Strip mining leaves the land virtually unrecognizable twice over. First, the surface miners themselves, in their moving of mountains, create a “lunar” landscape devoid of anything other than dirt, rocks, and coal. Then, in an attempt to return that landscape to nature, mine operators pack the dirt as tightly as possible into the form they see fit and plant all flora they can in hopes of preventing landslides. This process of reclamation, even when completed, leaves the land entirely different from any of its neighboring mountains, hillsides, and hollows. The land remains virtually flat, treeless, and more closely resembling a golf course than the Appalachian Mountains. As a result of this destructive power, generations of opposition have been born in Appalachia, and while they have led a well-warranted fight to end these practices, many in the region still support and advocate for strip mining.

As the practice has continued over the past 75 years, support for strip mining has become even more common than opposition. Although this divided viewpoint may seem contradictory since more strip mines equate to more disturbed land, the opposite effect has occurred because a higher number of strip mines means more jobs for miners, and this effect is only multiplied by the network of family and friends of each miner. Compounded by regional insecurities of employment and ties between masculinity and coal, the Cumberland Plateau region of Appalachia and eastern Kentucky has become enmeshed in strong, unquestioned support of any form of surface mining—even massive, invasive, and expensive operations such as mountaintop removal (MTR).[1]

Regardless of the region’s vocal support for strip mining, a few scholars have strongly rooted themselves in the perspectives of the opposition. The reasoning for this split can vary from author to author, but one of the most significant reasons comes from the historical evolution of strip mining in Appalachia. Unlike what can be found in the region today, strip mining in the mid-20th century was initially met with a serious, popular grassroots movement that sought an end to the industry. Historians, and consequently many other academics, have attached themselves solely to the opposition to strip mining and its historical evolution. That focus has prevented a proper explanation as to how and why such a vocal, community-driven opposition gave way to an equally vocal, community-based support for the industry by the 1980s. This turn in perspective is in no way meant to downplay the opposition, as they are as much a part of this history, if not more so, than the supporters of strip mining. Overall, this type of coal extraction reveals a dual narrative in which both the opposition and support rise due to strip mining’s pressure on the community. However, as local residents failed to stop the spread of strip mining by the early 1970s, miners were increasingly backed into an economic corner with little choice but to accept it and reject, often violently, any form of opposition.

Remaking the Land: Strip Mining in Practice

Strip mining in itself rests at an odd point in history: the range of methods and practices that could be considered strip mining, or surface mining as it is also commonly known, consists not only of the newest, most modern methods of mining but also some of the oldest and most primitive. Early colonists in America, lacking the European technology to develop traditional mines, mined coal directly from the seam with picks and shovels, and this method had no significant impact outside of local markets.[2] As the extraction of coal in Appalachia increasingly began to look like a certainty following the Civil War, industry speculators began to buy mineral rights through the broad-form deed, which separated ownership of the coal from ownership of the surface indefinitely—while also leaving any property taxes as the responsibility of the surface owner. Worse yet, the broad-form deed contained a clause that granted the mineral owner the right to extract the coal with nearly absolute impunity to any damages to the surface so long as it was “convenient” to the company. Although this clause later justified surface mining, most of the deeds were sold more than 50 years before strip mining was possible, and the sellers could not have even imagined its destructive force when signing over.[3]

During World War II, local residents, land owners, and the courts played a significant role in the development of strip mining as a common practice in the southern Appalachian Mountains, booming from just over 12,000 tons of coal produced by strip mines to nearly 1.5 million tons in 1946.[4] The temporary market conditions of World War II, amplified by the needs of U.S. allies, had created the boom necessary for strip mined coal to enter the market. However, the energy needs of a burgeoning post-war society that maintained its growth. The chief arbiter of this growth became the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a New Deal program created to tame the wild Tennessee River Valley and its flooding by capturing “its boundless energy works for the people who live in this valley.”[5] By 1953, though, the TVA’s exhausted hydroelectric dams were not solely capable of providing cheap energy to the people served by the agency, so it then turned to burning coal–specifically, strip-mined coal–to be produced far more cheaply and sold for much less than any coal mined from underground.[6] This shift fueled the spawn of what Harry Caudill coined as “the TVA Companies” that were dependent on the agency’s long contracts, which could reach upward of 15 years. These TVA Companies pioneered strip mining as a low-cost, high-profit alternative to the more traditional deep mines.[7]

Strip mining in Appalachia, in these early years, typically occurred at contour mining sites where the miners shaved off hillsides and left a highwall of rock exposed. After removing any overburden (timber, topsoil, and anything else in the way), the strip miners exposed the “bench,” the seam of coal adjoined to the highwall, which they mined up using heavy machinery—typically bulldozers.[8] A key limiting factor in the development of strip mining, then, was technology because it required such heavy, expensive machinery, which was only compounded by the rough terrain of eastern Kentucky’s mountains. Therefore, strip mining was slow to develop in the region and not only in the sense of the emergence of mines themselves but also in the practices they used. Thus, contour mining dominated for decades as the primary mode of surface mining in eastern Kentucky with any other method either being done in conjunction with a contour mine, such as auger mining, or having evolved from it as in the case of MTR.[9]

Not long into the widespread implementation of the strip mining method, Kentucky courts were ruling against mining companies and finding the practice of strip mining to be an inappropriate use of the broad-form deed.[10] In 1946, Treadway v. Wilson ruled that strip mining was an “oppressive” force, implying that the surface owners felt threatened by the practice and actively fought against it from its first uses.[11] Whatever the damages or threat of damages in these early cases, they paled in comparison to the horrors that companies unleashed once certain of their impunity. In 1953 in Buchanan v. Watson, Kentucky courts ruled that since the coal was the company’s property, they did in fact have the right to extract it by any means necessary, but they would also have to pay the landowner for damages to the surface. Despite the favorable ruling that still allowed them to strip, company officials and lawyers were outraged with this ruling and petitioned for a rehearing. In the rehearing, under pressure from lawyers and lobbyists connected to big coal, the court found that the company did not have to compensate the surface owner, citing the “relatively little value” of the land and the economic status of the coal industry.[12] With this ruling strip mining had finally gained the legal foothold in eastern Kentucky that it had needed to expand, and the tonnage produced from strip mining doubled from 1950 to 1960 with notable spikes following the ruling of Buchanan v. Watson and its rehearing.[13]

“Stirred to Action”: The Unified Front of Resistance in the 1960s

The wide-scale adoption of coal, such as with the TVA, provided a stable market for strip mining to continue its growth, but because of its volatile, environmentally disruptive nature, strip mining stunted its own growth by agitating and antagonizing Appalachian residents living near mines. By the mid-1960s, strip mining had grown large enough to be seen as a serious threat to eastern Kentucky. Describing the widespread damage of strip mining in central Appalachia, Harry Caudill’s My Land is Dying includes the personal account of Eva Ritchie (identified as Mrs. Bige Ritchie), who “saw a strip mine bulldozer uproot the coffin of her infant son from the backyard family cemetery and pitch it down the mountainside.”[14] Ritchie later told Kentucky Governor Edward “Ned” Breathitt, “I thought my heart would bust in my breast when I saw the coffins of my children come out of the ground and go over the hills.”[15] Although few others lacked the gravity of Ritchie’s account, the serious impediment to livelihood was becoming more and more apparent in Appalachia and so too did the notion that something must be done.

Anyone living in the vicinity of a strip mine, if they had not already been displaced by it, could feel its impacts. Perhaps the most strongly hit of any Appalachians were those who still practiced agriculture in what bit of land they might have retained in their hollow. Residents writing to their U.S. Representative Carl D. Perkins repeatedly denounced the practice of strip mining in this region due to its destructive effects on farmlands. Resident Curtis Cornett wrote to Perkins in 1967 asking for something to be done about strip mining because “the rocks come down and kill calves.”[16] In a similar, slightly more detailed, letter to Perkins, Russell Belcher accounted the damages that a company had done by strip mining near his house roughly five years earlier in 1965, including “big holes of [polluted] water and [they] some how caused [rock] slips [from the] highwall [coming] down in the pasture field.” Having just finally recovered from those damages to his homestead in 1970, he was ready to begin farming again, only after having “bought over 300 [dollars] in seeds and fertilizers” in addition to repairing a fence they damaged only to find that the company was preparing to return just as he restarted his farm. This time, however, Belcher was also worried for his “father-in-law who is 79-years-old… and has 4 cows on pasture here and sells milk… [and] if he has to sell his [cows,] I don’t see no chance for them to live.” [17]

By the late 1960s, even those well removed and far from the vicinity of a strip mine were beginning to feel the practice’s ecological effects. H.H. Robinson wrote to Perkins to express his fear that a recently constructed flood control reservoir was at risk of being silted up by strip mines farther down the stream. Pleading for government intervention to stop the mining method, he wrote, “A bill to end this destruction of mountain land would cost no one money but the people who sacrifice the land for quick profits.”[18] Rufus Reed, a naturalist and citizen of Lovely, Kentucky, summed up this growing sentiment by writing to Perkins after the Congressman’s public renouncement of strip mining that “the common people will be behind you 100%, as they are angered over the ruination of their lands, [and] also the roads by heavy coal trucks.” These descriptions offer the conditions that birthed the strong, loud, and popular opposition to strip mining, because regardless of how close they might live to a strip mine, eventually it would impact them in some capacity or another.

Mirroring the networks of kinship that uphold strip mining as viable employment in the 21st century, each infraction or impediment that a strip mine created against an Appalachian resident strengthened the opposition by fueling the expansion of its network. For these residents, there was no economic benefit in what they rightfully saw as a malignant encroachment on their property that violated their rights to it. In this sense, opposition to strip mining operated primarily, but not exclusively, as a form of commons environmentalism.[19] Rather than trying to preserve some idealistic, pristine wilderness, these residents were fighting to preserve the survival of commons resources and systems they heavily relied on, whether a farmer grazing cattle, horses, or hogs; a hunter depending on deer, turkey, or small game meat; an angler for bass, bluegill, catfish, crappie, or any other edible fish; or even a driver on heavily damaged public roads. For any of these people, the costs of strip mining to those economical resources and systems they so often depended on outweighed its profits, employment, or potential for economic development.

These converging factors lead to the creation of a visibly strong, fairly centralized, and geographically consistent grassroots movement in Kentucky by 1965. Dan Gibson, an 81-year-old coffin maker from Clear Creek, Kentucky, gave the inspiration and backbone needed to form such a centralized opposition that spring when defending the land of his stepson, who was serving in the Vietnam War, from the threat of a strip mine. Knowing that there was nowhere else he could turn, no place in the legal system that could adequately shield either him or the land, Gibson turned to his .22 squirrel rifle. He successfully held back bulldozer operators for several hours until he surrendered himself under promises from the Kentucky Oak Mining Company that they would not cross the property line along with reassurances from neighbors that they would not let them. Gibson, however, would serve hardly any time for his defense as the Knott County Jail was quickly surrounded by an armed mob demanding that he be released and his charges dropped, which county officials quickly met.[20] Harry Caudill immortalized this moment as the birth of the opposition, writing that “What was truly new about it was that several hundred mountain men and women…had been stirred to action by the realization that their culture, their way of life, and their long connection with the land were in danger.”[21] Caudill continued, “At a time when most of the highlanders had long ago surrendered to apathy, the inhabitants of Clear Creek Valley, and along with them those of several nearby communities, had resolved to fight. Thus it was that the Appalachian Group to Save the Land and People (AGSLP) was born.”[22]

Because of their strong local support, deeply rooted political connections, and their ability to capitalize on sympathy, AGSLP quickly became one of the most recognized and formidable factions in the opposition to strip mining. AGSLP acted rather quickly after its founding in June 1965, and by the end of the month they had gained an audience with the governor, having organized a 50-car, 200-mile motorcade to deliver to Frankfort a petition that had amassed 3,000 signatures charging strip mines of utterly destroying the land and demanding that action be taken.[23]Although the group had left embittered, with only a promise of new regulations if those in place were proven insufficient, they had at least managed to convince Governor Breathitt to visit Knott County to see the damages for himself. That same month the group led Breathitt on a “dusty two-hour tour of Knott County,” including several notable sites such as the Ritchie family cemetery, and by the end of his visit, Breathitt had been wholeheartedly convinced to join the fight and use the weight of his office to push for a quick and effective resolution.[24]

The fight continued through the year, but even with the help of the governor, it was an uphill battle. Governor Breathitt, shortly after his vow of aid, began a three-pronged attack on the issue by asking the TVA to provide reclamation funds, having state officials begin drafting new regulation laws, and calling for the state’s attorney general and his office to intervene in any cases on the issue, all of which he followed through on and even saw some success in.[25] At the grassroots level, on the other hand, the rest of the year passed rather quietly until November 1965. A recently widowed elderly woman from Lotts Creek named Ollie Combs came under threat of losing her land to a broad-form deed sold decades earlier by her father, which was quickly encroached on after her husband’s passing. Combs, known as the Widow Combs by most people who knew her, was ultimately able to rely on the rescue of Gibson, her neighbors, and AGSLP to defend her land from the dozers’ destruction.[26] Although this resistance held for a few days, the dozers returned at the first chance they could, and with nowhere to go and no one to turn to, Combs and her two sons defiantly held the bulldozer operators back themselves by lying in front of them on the eve of Thanksgiving. When Combs refused to surrender herself, local law officials packed them down the mountain for violating the company’s restraining order on her own property, and she and her two sons ate their Thanksgiving dinner in the Knott County Jail that year.[27]

Photos of Ollie Combs swept through the state, and within a month after her arrest, the news of her defiance also helped to bring the issue into the national spotlight with a lengthy New York Times article.[28] This publicity reinvigorated the momentum that AGSLP had initially found in June, and it also helped Governor Breathitt keep the issue in the forefront as officials under him continued working on legislation. By January, the Breathitt administration had finalized their regulatory bill, which had received favorable committee reports, and was preparing for three days of joint hearings with Ollie Combs scheduled to provide the final testimonial. And despite the three days of testimony from a wide range of influential leaders, it was Combs’s account of her trials and tribulations that stole the vote. Breathitt recounted years later that “when they got through that testimony, there wouldn’t a bit of noise in the house.” He continued, “It was very dramatic, and when she told her story, I saw some of my friends in the opposition [to the bill] in the gallery gather up and shake their heads [because] they knew they were beat.”[29]

While the Strip Mine Control Act in 1966 was certainly the most significant success of AGSLP to that point, there were also severe, unexpected consequences that came with it. Until 1966, the only legal backing to recognize strip mining as a legitimate form of mining came from court rulings and weak regulations that were entirely ignored, if not actually unknown. By convincing the state government to pass strong regulations with continued public awareness, AGSLP unknowingly gave many operators who were on the fence about it a greenlight to start strip mining. By the end of the decade coal production from surface mines would triple, and between the years 1965 and 1967 the number of strip-mining permits alone doubled, which caused the industry to grow at a far more rapid rate soon invading communities that had not yet been affected by strip mining.[30] Charles “Buck” Maggard, one of the more radical members of AGSLP, remembered the successful passage of the 1966 legislation as the group’s ultimate defeat in a 1990 interview, saying, “What really happened in 1966, instead of regulating strip mining, for the first time we made it legal.”[31] Maggard also suggested that the bill had received “the blessing of the coal operators,” and that their “crocodile tears” over the damage of this law to the industry were actually a crafty manipulation to weaken an already favorable regulation and validation of strip mining.[32] Either way, the consequences were irreversible and totally incomprehensible to AGSLP at the time.

Through the late 1960s, opposition to strip mining became increasingly more apparent in the region, and at the root of this growth was a constant expansion of the industry and the spilling over of its sheer destructive power. New groups and factions spread throughout eastern Kentucky, with most beginning locally and then spreading with an expanding network of grassroots opposition. Each of these groups had a separate agenda, philosophy, and strategy, but they all felt a mutual hatred of strip mining. However, these new groups, as they popped up, often became more violent or crafty in their attempts to stop strip mining. For example, AGSLP became fairly factionalized following the events of 1966 which led to the creation of the Mountaintop Gun Club (MGC). If this group knew that someone’s land was under threat of being stripped, they would lease the land from the owner to create a “shooting range” for as little as a dollar. This maneuver had the dual effect of protecting the land legally, since it would interfere with the broad-form deed and require litigation from the companies, while also maintaining a sense of extralegal vigilante justice, as those operators who did succeed in gaining the right to use the land would put their workers under constant threat of a “stray” bullet from one of MGC’s shooting ranges.

The Second Front: Declining Opposition and Rising Support into the 1970s

The key development in the expansion of opposition was that it was spreading to communities well removed from AGSLP’s sphere of influence in Knott and Perry Counties. Perhaps the largest and most significant of these new-wave groups was the Citizen’s League to Protect Surface Rights (CLPSR), which Joe Begley founded in 1970 in Letcher County with the intent to “join a little group in Knott County.”[33] To Begley, the most important part of determining CLPSR’s success was to “get out of Blackey” in Letcher County, through collaborating with a network of opposition and getting the destruction and chaos on “radio, and television, and the newspapers.”[34] CLPSR also became one of the most heavily populated and active of these opposition groups, amassing 300 members by 1972.[35] However, growth in the opposition also meant growth in the support of strip mining. The more that strip mine operators spread their destruction throughout the region, the more strip miners they hired and underground miners they fired. Even before the middle of the new decade, the rising support of miners desperate for employment reached a critical mass, which led to more and more suppression of any form of opposition.

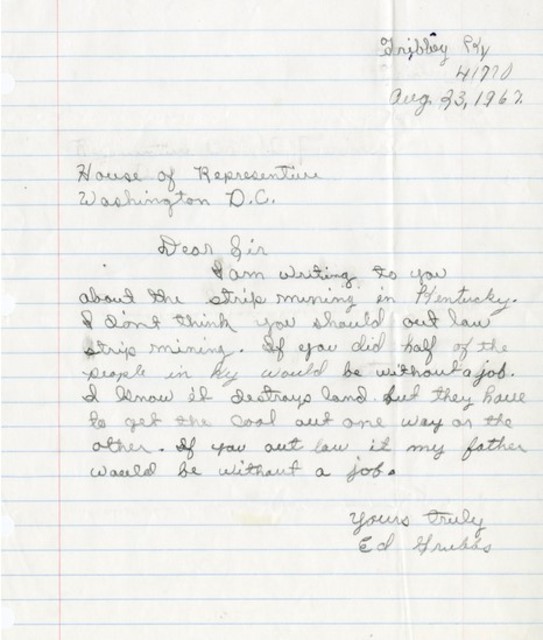

There was little support of strip mining outside of the operators and their cronies and between the miners and their families. The earliest letter in support of strip mining to come across the desk of Representative Perkins came in 1967–the only one in that year and nearly in that entire decade. The letter was written in the scrawl of a young child and read simply, “I know it destroys the land, but…if you outlaw it my father would be out of a job.”[36]

Figure 1. Letter from 11-year-old Ed Grubbs of Tribbey, Kentucky, to U.S. Representative Carl D. Perkins, explaining that strip mining should not be made illegal because his father would be without a job. Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Following the backfire of the 1966 regulations, the opposition to strip mining had largely realigned their goals from control to outright abolition of strip mining, which was still a feasible goal at the time and naturally would have frightened those involved in strip mining, but consequently this move also helped to alienate the strip miners living within the community.[37] Also, this letter began a trend of residents’ letters written in support of strip mining in which the author recognizes the damage, but they also embed within that acknowledgement a sense of desperation for work, a sense that there was nowhere else to turn.

However, these arguments were moot to the opposition because as they saw it, an abolition of strip mining would also mean a return to deep mining, which hired more people for longer periods, but at the cost of profits. Michael J. Halbert, a resident of Martin, Kentucky, summed up this viewpoint in a 1971 letter:

On the economic front, strip-mining is permanently destroying underground mining jobs. While we might experience a boom this year, the ultimate result will be the economic breakdown of our region. On the social front, these same men forced out of work will become additions to the welfare roles. The ruined mountain sides, the polluted streams, the silt-filled creeks, and the homes crushed by mud are the ultimate results of stripping. A region of ruined people and ruined land is the result of stripping.[38]

Perkins himself explained the issue in a far more light-hearted manner, writing in that same month to an aspiring journalist that “the bugaboo of unemployment” had no serious effect in eastern Kentucky because the people simply knew that it did not “involve an enormous amount of employment in the first place.”[39] This view that strip mining presented not only an ecological threat to Appalachia but also an economic one was what made opposition to strip mining so potent in this period, because the majority of people, with the exception of strip miners themselves, could find some fault somewhere with the practice. The opposition had grown so strong in this period that of all the letters, petitions, and organizations that crossed Perkins’ desk in the 92nd Congress, over 1,300 asked for abolition or control, while only 145–mostly miners given prewritten letters by their company–saw no fault in the practice as it stood.[40]

The movement was also being boosted by Appalachia’s particular spot in the national scene as well. The region had been brought to the forefront of America’s attention by the success of works such as Michael Harrington’s The Other America (1962) and Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands (1963), which inspired the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to launch the War on Poverty in 1964. Anti-poverty workers swarmed the region in this period with the aim of organizing local Appalachians around issues impacting their daily lives with the central goal of “maximum feasible participation of the poor.”[41] These anti-poverty workers had not played a role in the organizing of AGSLP, CLPSR, or similar grassroots groups, but their organizing happened almost concomitantly with the start of the War on Poverty. As historians have pointed out, local people’s deep understanding of their situation and their own willingness to resist it did more to radicalize anti-poverty workers than the other way around.[42]

Anti-poverty workers eventually joined and contributed directly to the growing opposition as the issue and practice expanded in 1966 and 1967. Even then, once anti-poverty workers were involved, namely the Appalachian Volunteers (AV), their role remained minimal within the opposition. Joe Mulloy, the AV field director in Pike County, stated that strip mining to the organization was simply just “the issue of the year…where we should be focusing our supportive efforts.” Therefore, the organization played only a mediator role between the multitude of grassroots organizations, media, and politicians.[43] Yet, this role must have seemed larger to coal operators as the AV funded and printed studies against strip mining, helped grassroots organizations attend or plan events and tours about the issue, and even inspired residents to fight off dozers in Pike County by founding a chapter of AGSLP.[44] Coal operators also stood to gain a strategic advantage by exaggerating the role of anti-poverty workers because they could brand them as outsiders and agitators, which helped undermine the efficacy of a predominantly grassroots movement to bring the practice to an absolute end in the minds of not only politicians but also more neutral Appalachian residents. Regardless, Mulloy differentiated himself from the civil disobedience that had come to define the opposition by stating plainly, “I was not holding my hand up in front of a bulldozer, I didn’t see that as my role.”[45]

Coal operators beginning to feel the pressure from this grassroots movement took more aggressive counter-measures. AGSLP had won two major victories in the summer of 1967 that warranted significant action from the operators: first, the Island Creek chapter of AGSLP in Pike County had succeeded in stopping a Puritan Coal Company strip mine at the property line of Jink Ray’s farm; then, in the same month AGSLP successfully organized a strip mine tour with state and federal officials to see the persistent damage in spite of the 1966 law.[46] To the operators, the former was likely more effective than the latter because AGSLP had gone from seeking regulation to abolition with the issue increasingly taking on national significance, which would have made the presence of federal officials, including representatives from the Department of the Interior who would likely oversee any federal regulation, seem all the more frightening. In August 1967 Pike County officials under the leadership of Commonwealth Attorney Thomas Ratliff, a native of Pike County and co-founder of the Independent Coal Operators’ Association (ICOA), placed Joe Mulloy and his two neighbors under arrest on sedition charges that branded them as communists.[47]

This move did not have any immediate impact on the fight against strip mining, because those already in the opposition saw through the sham and did not buy the “red scare” propaganda, which was a typical tactic for operators. In truth, the arrest was a follow-through on threats from the ICOA, who had made an earlier visit with the sheriff of Pike County to warn the Mulloys of the dangers faced by previous opponents, including a thinly veiled threat that one organizer had “got in his car and turned the ignition and it blew him up.”[48] Moreover, the issue of strip mining as a dangerous practice had largely been accepted as a federal one, so the fight was quickly changing. The arrest of Joe Mulloy first signaled this change on the other side of the aisle because leading up to the arrest, local people had consistently warned the Mulloy family of the “old days” and how local law would take outside union organizers and “dump them across the county line,” after killing them back in the 1920s and 1930s.[49]

Although the immediate effects of the Mulloy arrest seemed minimal, it still carried an impact on the movement that only grew over time. In particular, the loss of the anti-poverty workers strained the strip mining abolition movement because they were quintessentially a dedicated staff that helped establish critical communication networks, secured funding for travel outside of eastern Kentucky, and ultimately helped to bring the movement onto the national scene. Despite Joe Mulloy’s humble downplaying, the AV served a very serious and legitimate role in the movement. This impact was likely easy to minimize because of how it could present itself, such as the case of Tom Bethell, who ferried the 50-man tour of state and federal officials to and from a strip mine in his Jeep that bulldozer operators had thought they made inaccessible by damaging the roads.[50] AGSLP still did most of the heavy lifting in organizing this trip, even using their connections with Harry Caudill and Carl Perkins to help attract federal officials, but their effort would have been moot if it had not have been for Bethell because operators would have successfully camouflaged their operations.[51] While such a case may seem coincidental and maybe even trivial, AV support in manpower alone clearly had an effect in their brief involvement in the opposition and has left the nagging question of “what if?”

The sedition arrests also likely carried an effect on the strip mining abolition movement within the communities. This impact is best evidenced in Jessica Wilkerson’s To Live Here You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (2019), which highlights Edith Easterling, a resident of Pike County who worked closely with and even joined the AV but was socially isolated following the Mulloy arrest. In Easterling’s case, she had lost much of her respect among Pike Countians and had even left her church as rumors swirled about her involvement; however, much of the negative publicity that came from the sedition arrests was not a result of the allegations of communism but instead from the connection between the McSurelys, a married couple also charged with and arrested for sedition, and the national Civil Rights movement.[52] Easterling’s communal shunning, then, could have potentially come as much from this connection as it could have from her connection to the anti-strip mining movement.

As 1967 wound down, the opposition found itself somewhat in decline. The loss of the AV was one of the biggest setbacks that the grassroots movement had endured, but despite the coal operators’ accusations of outside rabble-rousing, the movement had not necessarily slowed down. The more serious damage was still to come because Breathitt’s term as governor was winding down and the election for his replacement had leaned in favor of the coal interests. As a final act on his last day in office, Breathitt signed orders that decreased the maximum slope of a mountain that could be strip mined from 33 degrees to 27, which was a move he felt confident in doing because he thought that the governor-elect “would no more dare to repeal these new regulations than he would be expected to put them in effect in the first place.”[53] Moreover, Breathitt had predicted correctly as Governor Louie B. Nunn neither enforced nor repealed any of the regulations, which helped precipitate yet another spurt of growth in strip mining that saw production tripled by 1970.

By 1968, the debate around strip mining had changed radically on the national scene despite dying down at the grassroots. Because of the rise of strip mining in coalfields around the country, this was now considered a national issue with politicians such as Robert F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall pushing for regulatory legislation.[54] However, as Perkins had warned AGSLP the previous year, the road to federal legislation was a long one filled with many major roadblocks like states’ rights, which he correctly predicted “could easily block passage for several years.”[55] Despite the significant progress in terms of awareness, AGSLP along with the rest of the opposition was fairly quiet in this period with no major protests in the year. Buck Maggard explained this sudden disappearance for himself and many fellow grassroots activists as a response to the rise of the Black Lung Movement, which was quickly catching local attention.[56] The most significant anti-strip mining display came that August when four unidentified assailants kidnapped a Round Mountain Coal Corporation nightwatchman and used the company’s dynamite to destroy nearly a million dollars’ worth of equipment in Leslie County.[57] This act was a significant departure from usual tactics of the opposition, hardly resembling the violence, or rather lack thereof, in demonstrations before and after. As theorized by activists in similar movements, like the Roving Pickets movement that fought to preserve the United Mine Workers Association hospitals (now Appalachian Regional Health), the explosion may have been a case of self-sabotage that dampened the movement’s image and awarded a fat insurance check to coal operators.[58]

Instead, the conflict between the opposition and miners usually consisted of flashing guns until bulldozer operators scattered. The most telling of these stories occurs in Appalshop’s A Tribute to Carl D. Perkins (1984), in which an unnamed young man recounts the story of an eastern Kentuckian intimidating a bulldozer operator attempting to work on the man’s land: “he starts tearing down his fence, you know, and the [Messer] guy comes out with his gun and propped it over the fence and said ‘you get down from that dozer, you on my land.’”[59] The landowner, most likely a native of Knott County and referring to AGSLP, continued: “I went over there, they called a special meeting one night, the people was all there and they all had guns and Carl Perkins got up front and said ‘Let’s calm down now…we should do things in an orderly manner and we should let the law handle things, I think.’”[60] Karen Mulloy recounted similar stories from her husband’s and her time working in the Island Creek community, as she remembered how “there would always be these old mountain men…always be up in the hills with their rifles…and if [the bulldozer operator] dare run over anybody they were going to kill [him].”[61] Violence, then, was typically used as an intimidation tactic, which would either temporarily force dozers off the land or insure the safety of non-violent, civilly disobedient, and highly visible protestors. Such a method of protest strongly resembled the community self-defense approach of groups like the Black Panthers, the Chicano Movement, and the American Indian Movement.[62]

After a few more rather passive years, the issue of strip mining fully emerged again when another boom hit in 1970. After persuading the Knott County government to declare strip mining a “public nuisance,” AGSLP appeared again in national newspapers for convincing the same officials to outlaw strip mining throughout the county in a 3-2 vote.[63] Sid Williams, the county judge responsible for the tie-breaking vote, attempted to invoke his right to a 30-day decision-making period, but a crowd of roughly 300 people rushed to the railings and forced a vote.[64] This advocacy illustrated the AGSLP’s power to act at the local level, where their power was far better concentrated and therefore all the more influential. Nonetheless, these county-level decisions show that in spite of the movement’s relative quietness, the grassroots group was just as popular as it had been when dozers invaded Ollie Combs’s land in 1965.

The opposition continued its work locally throughout this period until the issue finally peaked on the national stage in the 92nd Congress in 1971. Three major bills appeared in Congress that year, and while there were federal regulation bills as early as 1968, the 92nd Congress seriously contemplated regulation bills.[65] The first of these bills, H.R. 4556, proposed a total abolition of strip mining and was the only of these bills to be sponsored by an Appalachian state’s senator, West Virginia’s Ken Hechler.[66] AGSLP and CLPSR threw their full weight in favor of Hechler’s abolition bill, and that support, combined with a handful of individuals and concerned residents, made the Hechler bill the most popular of the strip-mining legislation in eastern Kentucky.[67] Despite this grassroots support, coming from one of the most directly impacted regions, the idea of abolition seemed too radical at the national level.[68]

Instead, the focus on the national scene fell to the two committee bills released that same year. Senate Bill 630 was particularly weak and lax in regulating coal companies, but given that these companies did not want to be regulated at all, the industry fought against any kind of legislation through the “bugaboo of unemployment.”[69] The House’s second strip-mining bill, H.R. 6482, on the other hand, was the strongest and most legitimate of the pending legislation. Despite the strength of the bill on the national stage, there was little focus on it from eastern Kentuckians. In fact, outside of the core opposition groups, such as AGSLP or CLPSR, there seemed to be minimal knowledge of what was happening within Congress, but a greater influx of letters written to Perkins indicated that eastern Kentuckians were aware that the issue had been handed off from the state to the federal government.[70]

The quantitative challenge with these letters, though, is that many of them came from groups and organizations not dedicated to the issue with an unknown, but presumably sizable, number of supporting members. The American Legion of Letcher County, for example, wrote to Perkins to “beg [his] vote and influence against strip mining.”[71] Similarly, the Floyd County Fish and Game Club wrote that “strip mining is a complete destruction of what all sportsmen's clubs are trying to improve.”[72] Even a representative of the local Girl Scouts troop wrote to Perkins about how “the devastation…was unbelievable to these young girls. I couldn’t explain very well why our government had allowed this to happen. At that time they decided to see what they could do to help save our environment.”[73] Later that same year one of the Girl Scouts themselves, 13-year-old Kim Roberts, wrote to Perkins to express her frustrations in their fight against strip mining: “We were told by people like [Governor] Julian Carroll and many different people that ‘we are going to do something.’ ‘We are proud of the Girl Scouts and what they are doing to abolish strip mining,’ but that’s just talk.”[74] She concluded her letter with an acknowledgement that the issue had transferred hands by writing, “We have done the best we can. Now [it’s] your turn.”[75] Strip mining had clearly penetrated the livelihoods of virtually all eastern Kentuckians, including anglers, hunters, veterans, and 13-year-olds, illustrating that the residents of this region were almost entirely opposed to the practice.

Despite this strong sentiment, however, the main organizations in the opposition faced a strengthening support of strip mining from the miners themselves that helped to undermine the role of grassroots activism on the national stage. This deepened support manifested in January 1972 when AGSLP, in conjunction with several other organizations, attempted to protest an operation in Elijah Fork of Knott County.[76] They had justified the end of the operation as a means “to show the legislature if something is not done, we’ll do it ourselves.”[77] However, despite the AGSLP’s plan to stay at the operation indefinitely, the miners and guards of the company took matters into their own hands by meeting the opposition with outright violence. The men threatened to rape the women camping out on the mountainside operation, menacing the protestors to the point that one of the strip miners rushed to their side to provide some safety, and miners at the bottom of the hill busted windows, slashed tires, and flipped some cars.[78] The defeated AGSLP soon retreated off the mountain.

This event was essentially the last major protest from AGSLP, and it also signaled a new era in the fight over strip mining because the miners themselves took an active role against the opposition. Although this role was certainly a menacing one that bullied the opposition into submission, it signaled that the miners themselves were involved in the matter, and even if the “bugaboo of unemployment” meant little to the opposition, it clearly was no longer the case with the men employed in the strip mines.

While the cries of unemployment were once extraordinarily exaggerated, they were becoming increasingly real warnings from the miners’ employers. Not only did this make these claims all the more credible to miners than to any neutral or oppositional parties but also justified the miners’ turn toward violent and extreme measures by the miners. By 1974, despite record-breaking profits brought on by a nation-wide energy crisis, industry leaders estimated the region had lost at least 5,000 jobs in that same year alone.[79] This undercurrent of economic hardship was only made harder by the growing damage to the region’s natural ability to offset it as previous generations had with game, fish, livestock, and other commons practices like gathering herbs, berries, and nuts. For these miners, there seemed to be no alternative livelihood. In the decades since, support for strip mining has only become more widespread as violence against opposition persists and keeps many Appalachians from even beginning to question strip mining, its irreversible effects, and the nature of the region’s economic dependency to it.

Bibliography

“4 Hunted After Leslie Mine Blasts.” Courier-Journal, August 28, 1968, B1. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/109473149/?terms=4%20Hunted%20After%20Leslie%20Mine%20Blasts&match=1.

Ashley, Frank. “Women Pickets Seek to Shut Down Knott County Strip Mine.” Courier-Journal, January 21, 1972. https://www.newspapers.com/image/107808272/?terms=Woman%20Pickets%20Attempt%20to%20Shut%20Down%20Strip%20Mine&match=1.

Baldridge, John R. 1972. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Begley, Joe T. 1972. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Begley, Joe T. Interview by Margaret Brown. Appalachia: War on Poverty Oral History Project. Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. June 4, 1991. Audio, 2:07:19. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt79zw18nc6q.

Belcher, Russell. 1970. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box D-079. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Branscome, James. “Appalachia–Like the Flayed Back of a Man.” New York Times, December 12, 1971, SM30. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/historical-newspapers/appalachia-like-flayed-back-man/docview/119046461/sem-2?accountid=10628.

Caudill, Harry. 1967. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box D-064. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Caudill, Harry M. My Land is Dying. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1971.

Cornett, Curtis. 1967. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box D-064. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Crase, Tilden. 1971. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Davis, Dee, and Anne L. Johnson, dir. A Tribute to Carl Perkins. Whitesburg, Kentucky: Appalshop, 1984.

Eller, Ronald D. Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012.

Franklin, Ben A. “Critics of Strip Mining Are Stepping Up Resistance.” New York Times, May 10, 1970. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/historical-newspapers/critics-strip-mining-are-stepping-up-resistance/docview/119088435/sem-2?accountid=10628.

Franklin, Ben A. “Kentucky’s Governor Joins ‘War’ on Strip Mining.” New York Times, December 19, 1967. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/historical-newspapers/kentucky-s-governor-joins-war-on-strip-mining/docview/117054712/sem-2?accountid=10628.

Franklin, Ben A. “Strip Coal Mines Vex Kentuckians: 70 Hold Motorcade, Picket Capitol, and See Governor.” New York Times, June 23, 1965. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/historical-newspapers/strip-coal-mines-vex-kentuckians/docview/116894203/sem-2?accountid=10628.

Gibson, Dan. 1972. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Greider, William. “Kentuckians Score New Federal Strip-Mine Bill.” Courier-Journal, March 12, 1968. https://www.newspapers.com/image/109388902/?terms=Kentuckians%20Score%20New%20Federal%20Strip-Mine%20Bill&match=1.

Grubbs, Ed. 1967. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box D-064. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Halbert, Michael J. 1971. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Hazard Coal Operators Association. 1972. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

“Kentucky County Bans Strip Mines.” New York Times, June 8, 1970. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/historical-newspapers/kentucky-county-bans-strip-mines/docview/118866777/sem-2?accountid=10628.

Kirby, Richard M. Interview by Margaret Brown. Appalachia: War on Poverty Oral History Project, Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. March 12, 1991. Audio, 1:45:38. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7dr785kg0d.

Lewis, Ann, dir. To Save the Land and People. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1999.

Lilienthal, David E. TVA: Democracy on the March. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1944.

Luigart, Fred W., Jr. “Senator Charges Kennedy Visit ‘Blackened’ State Image.” Courier-Journal, February 16, 1968. https://www.newspapers.com/image/109387288/?terms=Senator%20Charges%20Kennedy%20Visit%20%27Blackened%27%20State%20Image&match=1.

Maggard, Charles. “A Conversation with Charles ‘Buck’ Maggard.” Rutherford Living History. August 18, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2B-mzP97Fw.

Maggard, Charles. Interview by Thomas Kiffmeyer. Appalachia: War on Poverty Oral History Project. Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. November 29, 1990. Audio, 1:23:33. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7ngf0mv755.

Marx, G.T., and Dane Archer. “Community Self-Defense.” Society (New Brunswick) 13 (1976): 38-43.

McNeil, Bryan T. Combating Mountaintop Removal: New Directions in the Fight Against Big Coal. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Montrie, Chad. “‘To Have, Hold, Develop, and Defend’: Natural Rights and the Movement to Abolish Strip Mining in Eastern Kentucky.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 11 (2005): 64-82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41446655.

Montrie, Chad. To Save the Land and the People: A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Montrie, Chad. “‘We Mean to Stop Them, One Way or Another’: Coal, Power, and the Fight Against Strip Mining in Appalachia.” In Mountains of Injustice: Social and Environmental Justice in Appalachia. Edited by Michele Morrone and Geoffrey L. Buckley, 81-98. Athens: University of Ohio Press, 2011.

Mulloy, Joseph T. Interview by Thomas Kiffmeyer. Appalachia: War on Poverty Oral History Project. Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. November 10, 1990. Audio, 3:11:55. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7mkk94987b.

Mulloy, Karen B. Interview by Thomas Kiffmeyer. Appalachia: War on Poverty Oral History Project. Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries. November 10, 1990. Audio, 3:07:24. https://kentuckyoralhistory.org/ark:/16417/xt7d7w675c69

Munn, Robert. “The Development of Strip Mining.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 3 (1975): 87-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40932084

Perkins, Carl D. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, box C-113, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Perkins, Carl D. Letter to Daniel Kaufman, October 29, 1971. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, box C-113, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Perkins, Carl D. Letter to Morris Shepherd, August 10, 1967. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, box D-064, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Portelli, Alessandro. They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History. New York City: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Roberts, Kim. Letter to Carl D. Perkins, May 31, 1972. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Robinson, H.H. Letter to Carl D. Perkins, March 23, 1970. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box D-079, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Scott, Rebecca R. Removing Mountains: Extracting Nature and Identity in the Appalachian Coalfields. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Sharbutt, Jay. “Strip-Mining Reform Failing in Congress.” Courier-Journal, August 18, 1968. Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/109470949/?terms=Strip-Mining%20Reform%20Failing%20in%20Congress&match=1

Shepherd, Morris. Letter to Carl D. Perkins, August 7, 1967. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box D-064, Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

“Strip-Mine Curb Seen in Kentucky: Gov. Breathitt Called Ready to Sign Controversial Order.” New York Times, December 9, 1967. https://www.nytimes.com/1967/12/10/archives/stripmine-curb-seen-in-kentucky-gov-breathitt-called-ready-to-sign.html

“Strip Mine Foes Blocked on Tour: Excavations Harass Group of 50 in Eastern Kentucky.” New York Times, July 30, 1967.

“Strip Mining in Kentucky: Mountaineers Say It Kills Their Land: Breathitt Vows Strip Mine Curbs, Says State Will Intervene in Cases on Mineral Rights.” New York Times, July 1, 1965.

Vance, Kyle. “Knott County Outlaws Strip Mining As a Test of Its Regulatory Power.” Courier-Journal, June 7, 1970.

Wallace, Patty F. 1972. Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, Box C-113. Special Collections and Archives, Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Richmond, Kentucky.

Wilkerson, Jessica. To Live Here You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2019.

[1] The cultural context necessary to understand these ideas in far greater detail is in Scott, Removing Mountains, 11-12, 81.

[2] Munn, “The Development of Strip Mining,” 87.

[3] Montrie, “To Have, Hold, Develop, and Defend,” 65.

[4] Ibid, 92.

[5] Lilienthal, TVA, 3.

[6] Montrie, To Save the Land, 70.

[7] Caudill, My Land is Dying, 72-73.

[8] Montrie, To Save the Land and the People, 22-23.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Caudill, My Land is Dying, 65.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Munn, “The Development of Strip Mining,” 92-93.

[14] Caudill, My Land is Dying, 75.

[15] Branscome, “Appalachia,” New York Times.

[16] Cornett, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[17] Belcher, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[18] Robinson, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[19] For more recent information on such environmentalism see McNeil, Combating Mountaintop Removal: New Directions in the Fight Against Big Coal (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 138-41.

[20] Montrie, To Save the Land, 72-73.

[21] Caudill, 76.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Montrie, To Save the Land, 75; Franklin, “Strip Coal Mines Vex Kentuckians.”

[24] Montrie, To Save the Land, 76; Franklin, “Strip Mining in Kentucky.”

[25] Montrie, To Save the Land, 77-78.

[26] Ibid, 79.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Franklin, “Kentucky Governor Joins ‘War’ on Strip Mining.”

[29] Lewis.

[30] Munn, “The Development of Strip Mining,” 93; Montrie, To Save the Land, 85.

[31] Maggard, interview.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Begley, interview.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Begley, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[36] Grubbs, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[37] Shepherd, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[38] Halbert, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[39] Perkins, Letter to Daniel Kaufman, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[40] Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, box C-113.

[41] Wilkerson, To Live Here You Have to Fight, 35.

[42] Eller, Uneven Ground, 135-36.

[43] Mulloy, interview.

[44] Wilkerson, To Live Here You Have to Fight, 57; Kirby, interview.

[45] Mulloy, interview.

[46] Montrie, To Save the Land, 91-93.

[47] Wilkerson, To Live Here You Have to Fight, 57-58

[48] Mulloy, K., interview.

[49] Ibid.

[50] “Strip Mine Foes Blocked,” New York Times.

[51] Caudill, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[52] Wilkerson, To Live Here You Have to Fight, 58-59.

[53] “Strip-Mine Curb Seen in Kentucky,” New York Times.

[54] Luigart, “Senator Charges Kennedy Visit ‘Blackened’ State Image,” Courier-Journal.

[55] Perkins, Letter to Morris Shepherd, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[56] Maggard, “A Conversation with Charles ‘Buck’ Maggard.”

[57] “4 Hunted After Leslie Mine Blasts,” Courier-Journal.

[58] Portelli, They Say in Harlan County, 270-76.

[59] Davis and Johnson, A Tribute to Carl Perkins.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Mulloy, K., interview.

[62] Marx, “Community Self Defense,” 38-43.

[63] Franklin, “Critics of Strip Mining”; “Kentucky County Bans Strip Mines.”

[64] Vance, “Knott County Outlaws Strip Mining.”

[65] Sharbutt, “Strip-Mining Reform Failing in Congress,” Courier-Journal.

[66] Montrie, To Save the Land, 138.

[67] Begley, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[68] Montrie, “We Mean to Stop Them,” 88.

[69] Hazard Coal Operators Association, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[70] Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers, box C-113.

[71] Crase, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[72] Baldridge, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[73] Wallace, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[74] Roberts, Letter to Carl D. Perkins, Carl D. Perkins Congressional Papers.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Montrie, To Save the Land, 104.

[77] Ashley, “Women Pickets Seek to Shut Down Knott County Strip Mine,” Courier-Journal.

[78] Montrie, To Save the Land, 104-05.

[79] Vance, “Knott County Outlaws Strip Mining As a Test of Its Regulatory Power,” Courier-Journal.