Chapter 6

Conducting a Critical Belief Analysis:

A User’s Manual

Checklists for Conducting a Critical Belief Analysis

This chapter leads the reader through a systematic process for conducting a Critical Belief Analysis (CBA). Chapter 7 provides an example analysis. Before conducting a CBA, the analyst must thoroughly understand the conceptual material in Chapters 2 through 5. If the analyst is uncertain about the basic concepts of CBA, they should seek to resolve their concerns. Those who wish to enhance their understanding of these concepts may find it helpful to read these articles and complete the exercises at the end of each article.

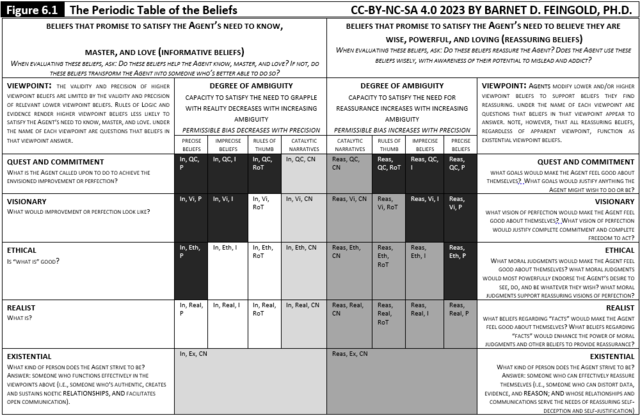

The analytic process is easier and more informative if conducted with the aid of The Periodic Table of the Beliefs (Figure 6.1). A larger, easier-to-read, scalable and printable version of “The Periodic Table of the Beliefs” is available as a Resource below the Table of Contents on the Projects page. The Periodic Table is designed to help analysts visualize the nature and limitations of the guidance beliefs provide, the relationships between beliefs, and the implications of disparities between agents’ and objective observers’ views of those beliefs. Analysts are encouraged to refer frequently to Figure 6.1 when conducting CBAs.

Each cell of The Periodic Table of the Beliefs is home to beliefs with a specific combination of fundamental need (motivation), precision/ambiguity, and viewpoint. Informative beliefs occupy the left half of the table while reassuring beliefs occupy the right. More precise informative beliefs can be found toward the left edge of the table while more precise reassuring beliefs can be found toward the right edge. More ambiguous beliefs can be found closer to the center. Lower-viewpoint beliefs are toward the bottom of the table; higher-viewpoint beliefs are toward the top.

The cells of The Periodic Table of the Beliefs are color-coded. Black cells share a distinctive combination of attributes: (a) agents may assume that beliefs possess combinations of characteristics that render them proper to those cells, but (b) those cells are actually vacant because their defining characteristics are incompatible. Light gray cells are home to beliefs that function as informative catalytic narratives, while dark gray cells are home to beliefs that function as reassuring catalytic narratives. White cells are home to those rare beliefs whose guidance will likely help agents achieve their goals.

Three additional checklists are also employed in conducting a CBA:

- Figure 6.2, Critical Belief Analysis Procedure, offers a detailed, systematic process that analysts can use to identify differences between the guidance agents assume their beliefs provide and the guidance their beliefs actually provide. It also helps analysts understand and, where appropriate, predict the consequences of those differences.

- Figure 6.3, Critical Belief Analysis Worksheet, is designed to help analysts document their progress and record their findings as they carry out a CBA in accordance with Figure 6.2.

- Figure 6.4, Identifying the Desires Motivating Beliefs, is a 23-item questionnaire designed to help analysts determine whether an agent’s attitude toward and treatment of an actual (observed) belief renders the belief informative, reassuring, or both.

Figure 6.2 | Critical Belief Analysis Procedure | |

Critical Belief Analysis (CBA) is devoted to answering the question, “How closely does the guidance a belief actually provides resemble the guidance the actor/believer/decision-maker (hereafter agent) assumes it provides?” This step-by-step procedure is designed to help the analyst find this answer. This procedure is intended to be used in conjunction with Figure 6.1, The Periodic Table of the Beliefs; Figure 6.3, Critical Belief Analysis Worksheet; and Figure 6.4, Identifying the Desires Motivating Beliefs. Figure 6.3, Critical Belief Analysis Worksheet, provides spaces in which to record both your analytic findings and the processes by which you reached them. Step 1: Orient Yourself to the Project.1. Record the research purpose and research question on Figure 6.3, the Critical Belief Analysis Worksheet. [1] 2. Identify the agent and the agent’s to-be-evaluated (target) belief(s). (Note: Each target belief requires a separate analysis.) 3. Collect and document requisite sources of information and context. [2] 4. Describe the circumstances in which the target belief developed if this description contributes to understanding the belief. 5. Complete a psychobiography of the agent(s). [3] 6. Specify the target belief’s second-order precepts (i.e., the rules determining how agents — and, if the agent is powerful, the agent’s subjects — are expected to think about, defend, criticize, and communicate about the target belief.) 7. List situations in which the target belief strongly influenced the agent’s past thoughts, feelings, policies, or actions. Describe (a) the results of policies, etc., shaped by the target belief(s) and (b) the agent’s responses to failures or unexpected consequences of those policies, etc. 8. List situations in which the target belief seems likely to influence the agent’s future thoughts, feelings, policies, or actions. Step 2: Locate the Belief on Figure 6.1, The Periodic Table of the Beliefs.Note: Locating the target belief on the Periodic Table requires the analyst to determine what the agent perceived, assumed, thought, or knew. However, the analyst is unlikely to have access to specific information about these matters. As such, the analyst may need to use the results of the information and context search (Step 1, #3), the psychobiography (Step 1, #5), and the agent’s writings, speeches, conversations, and actions (Step 1, #7) to “see the world through the agent’s eyes.” 1. Using the guidelines below, identify the cell of Figure 6.1 that the agent assumes the target belief to occupy. (Note: This approach to determining the agent’s assumptions about the target belief presumes those assumptions to have been consistent. If those assumptions have varied, more weight should be given to the agent’s recent assumptions about that belief in situations that, from the agent’s point of view, are similar to the situation(s) of interest.) a. Determine whether the agent assumes the belief to be informative or reassuring. Choose the option best describing what the agent expected the belief to do in the situations listed in Step 1, #7. (Note: Agents may look to a belief to assist them in multiple ways in a particular situation.) Determine if the agent expected the belief to:

Tally the number of times the agent looked to the belief for information (i.e., assumed the belief to be informative) or for reassurance (i.e., assumed the belief to be reassuring). Using this tally, determine whether the agent typically assumed that the belief offered information, reassurance, or both. (Note: If, in recent situations similar to the situation of interest, the agent assumed that the target belief was informative, the analyst is advised to presume the agent continues to consider it informative..) b. Determine the viewpoint of the issue the agent assumed the belief addressed. Viewpoints are hierarchically arranged on Figure 6.1, The Periodic Table of the Beliefs, from Existential (lowest) to Realist, Ethical, Visionary, and Quest and Commitment (highest). Identify the viewpoint of the issue the agent assumed the belief addressed in each situation listed in Step 1, #7 (see Figure 6.1). Determine if the agent’s words described or their actions manifested:

Tally the number of times the agent’s words or actions indicated they assumed the target belief addressed issues proper to each viewpoint. Identify the most influential viewpoint the agent assumed the target belief to occupy. (Note: If, in recent situations similar to the situation of interest, the agent assumed that the target belief addressed issues in diverse viewpoints, the lowest of those viewpoints is likely to be the most relevant for the purposes of this analysis.) c. Determine whether the agent assumed the target belief to be precise, imprecise, a rule of thumb, or a catalytic narrative. In each situation identified in Step 1, #7, identify the confidence the agent assumed the belief’s guidance merited. Determine if the agent’s words and actions suggest that they:

Tally the number of times the agent arguably assumed the target belief to possess each degree of precision. Specify the degree of precision that, for the purposes of this analysis, the agent is most appropriately viewed as assuming the belief to possess. (Note: If, in recent situations similar to the situation of interest, the agent assumed the target belief possessed diverse degrees of precision, the most precise of those is likely to be the most relevant to this analysis.) d. Summarize the agent’s assumptions about the target belief by circling or bolding the appropriate fundamental need, viewpoint, and degree of precision/ambiguity on the Figure 6.3 worksheet. e. Designate the cell of Figure 6.1 corresponding to the agent’s assumptions about the target belief with an “A” (for assumed). 2. Using the guidelines below, determine the cell of Figure 6.1 that the target belief actually occupies. (Notes: (1) Successful completion of this section requires an accurate and comprehensive understanding of CBA. (2) This approach to determining the nature of the guidance the target belief actually provides assumes the nature of that guidance has been consistent. If it has been inconsistent, more weight should be given to the guidance the target belief provided recently, in situations that, from the agent’s point of view, are similar to the situation(s) of interest.) a. Using the procedure specified in Figure 6.4 and other relevant information, determine whether the agent’s overall treatment of the belief facilitates the provision of information, reassurance, or both. If the belief is:

b. Identify the viewpoint of the issue(s) the target belief actually addresses.

Note: If, in recent situations similar to the situation of interest, the target belief addressed issues proper to the Existential Viewpoint, it should be treated as an Existential Viewpoint belief for the purposes of this analysis. If the belief addressed issues proper to a single non-Existential viewpoint, it should be treated as proper to that viewpoint. If it addressed issues proper to diverse viewpoints (other than the Existential Viewpoint), it should be treated as proper to the highest of those viewpoints.

c. Determine the precision of the target belief. First, identify the maximum possible precision of the target belief by considering the two constraints discussed below: Constraint #1: Viewpoint-imposed limitations on precision:

Constraint #2: Limitations on the precision of target beliefs imposed by the viewpoints of underlying beliefs: First, identify lower-viewpoint beliefs that the agent has explicitly cited (or that you [the analyst] can confidently specify) as providing crucial support for the target belief. The target belief cannot be more precise than the least precise of those beliefs. Next, using the guidelines below, identify the maximum precision of the target belief in each of the situations identified in Step 1, #6, and Step 1, #7 above.

d. Summarize your findings regarding the guidance the target belief actually provides by circling the appropriate fundamental need, viewpoint, and degree of precision/ambiguity on the Figure 6.3 worksheet. e. Designate the appropriate cell on Figure 6.1 with an “O” (for observed, actual) and check the appropriate circle on the Figure 6.3 worksheet. Step 3: Assess Existential Viewpoint Issues.1. If the target belief is either actually or assumed to be reassuring, an informative catalytic narrative, or an informative Existential Viewpoint belief, investigate the issues below. Record your answers to the questions below in the allotted spaces on the Figure 6.3 worksheet. If the target belief engenders no Existential Viewpoint expectations and has no effect on Existential Viewpoint functioning, proceed to Step 4. 1. 2. Determine the target belief’s impact on Existential Viewpoint functioning. a. How does the target belief affect the agent’s genuineness? Does it encourage or discourage (see Figure 5.1):

b. How does the target belief affect the quality of the agent’s noetic relationships? Does it encourage the agent to:

c. How does the target belief affect the quality of the agent’s communication? Does it encourage or discourage commitments to:

d. What is the overall impact of the agent’s genuineness, noetic relationships, and communication style/discourse ethics on the: (Record the assessments in the designated space on the Figure 6.3 worksheet.)

Step 4: Assumption-Reality Disparities and their Implications.1. Identifying the target belief’s assumption-reality disparities requires reflecting on the disparity between (a) the agent’s assumptions about the fundamental needs that motivate their acceptance of the target belief and the fundamental need(s) that actually motivate the belief’s acceptance, (b) the agent’s assumptions about the viewpoint of the issue the belief addresses and the viewpoint of the issue the belief actually addresses, and (c) the agent’s assumptions about the precision of the belief’s guidance and the actual precision of that guidance. The Figure 6.3 worksheet provides space to record insights into those disparities. a. Assumption-reality disparities regarding motivation. Identify the disparities between the agent’s assumed and actual motives for holding the target belief. Complete the following sentences: “The agent assumes they accept this belief because it satisfies their desire for . . .” “The agent actually accepts this belief because it satisfies their desire for . . .” If the agent’s assumed and actual motives differ, describe the likely consequences of this error by completing the statement: “This misapprehension matters because . . .” b. Assumption-Reality Disparities Regarding Viewpoint. Identify the disparity between the viewpoint of the issue the agent assumes the target belief addresses and the viewpoint of the issue the target belief actually addresses. Complete the following statements: “The agent assumes the target belief is concerned with . . .” (Complete this statement in a way that highlights the target belief’s assumed viewpoint.) “In fact, the target belief is concerned with . . .” (Complete this statement in a way that highlights the target belief’s actual viewpoint.) If the assumed and actual viewpoints of the target belief differ, complete the statement below: “The agent’s misapprehensions about the viewpoint of the target belief matter because (Specify likely errors.) . . .” Note: If the agent accurately assumes the target belief to be informative, see the Chapter 4 section, “The Value of Attention to Viewpoint and Viewpoint-Precision/Ambiguity Interaction in Security Analysis. If the target belief — whether informative or reassuring — is proper to the Existential Viewpoint or the agent assumes it to be, complete the following statements: “The agent assumes this belief will help them become someone who . . .” “However, it actually encourages the agent to become someone who . . .” If the agent’s expectations regarding the existential impact of the target belief conflict with reality, complete the statement below: “The ways this belief falls short of the agent’s expectations about its impact matter because . . .” c. Assumption-Reality Disparities Regarding Precision/Ambiguity. Identify the disparities between the precision of the guidance the agent assumes the belief provides and the precision of the guidance the belief actually provides by completing the following statements: “The agent assumes the guidance the target belief provides is . . .” (Describe the guidance the agent views the belief as providing, highlighting its assumed precision.) “In fact, the guidance the target belief provides is . . .” (Describe the guidance the belief actually provides, highlighting its precision.) If the agent’s assumption regarding the precision of the target belief’s guidance is inaccurate, specify the probable consequences of this misapprehension by completing the statement: “This misapprehension matters because . . .” Ensure all insights generated by Step 4 are recorded on the Figure 6.3 Step 5: Consequences, Self-Critique, Analytic Narrative.1. Describe the major consequences of the agent’s false assumptions about the target belief by completing the statement below. Where relevant, describe the effects of the agent’s belief-relevant second-order precepts and Existential Viewpoint functioning. “The most important consequences of the agent’s false assumptions regarding the target belief appear to be . . .” Note: Be sure to consider the likely impact of the belief’s second-order precepts and the agent’s Existential Viewpoint functioning [assessed in Step 3] on each of the identified implications or consequences. 2. Critique the agent-focused CBA. Upon completing a CBA of an agent’s belief, the analyst should conduct a self-critique of that CBA. While such self-critiques address the same factors as agent-focused CBAs — fundamental need, viewpoint, and precision/ambiguity — they are significantly easier to carry out. That’s because analyst-focused CBAs need only compare the analyst’s CBA of the agent’s belief with the standards by which such products are judged. Thus, the statement that analysts’ self-critiques should address is, “My CBA of the agent’s target belief meets the standards such analyses are expected to satisfy.” There are three such standards. First, security analysts are expected to strive for objectivity. In the language of CBA, security analysts are expected to do their best to ensure their reports are shaped by the desire for information rather than the desire for reassurance. Analysts are therefore advised to reflect on their thoughts and feelings about the agent-focused CBA and to review Figure 6.4, Identifying the Desires Motivating Beliefs, to sensitize themselves to any attitudes, beliefs, or practices that may have compromised their objectivity. Specifically, analysts should identify and document the potential impact of every Figure 6.4 “A” statement with which they agreed or strongly agreed. The products of their self-examination should be documented by completing the sentence stem, “Self-examination (including the use of Figure 6.4 to help uncover my possible biases) suggests the following attitudes, beliefs, or penchants, motivated by the need for reassurance, may have biased my conclusions:” Analysts should consider revising their agent-focused CBA if a review of Figure 6.4 raises the possibility of significant bias. If a review of Figure 6.4 suggests the possibility of mild bias, analysts should acknowledge that bias and discuss its possible impact on their conclusions. Second, the conclusions of competent, ethical security analysts are expected to be proper to the Realist Viewpoint. Analysts should strive to provide decision-makers with objective descriptions of the substantive and structural characteristics of agents’ beliefs and the implications of those characteristics. They should refrain from opining about the goodness of those characteristics or other issues that are not proper to the Realist Viewpoint. Analysts who discover that the conclusions of their CBAs are proper to the Existential, Ethical, Visionary, or Quest and Commitment viewpoints are advised to consider revising their reports. Finally, analysts are expected to be sensitive to the ambiguity of the explanations and predictions their conclusions inspire. Suppose such explanations and predictions are unfalsifiable. In that case, analysts should acknowledge that their conclusions are catalytic narratives, i.e., assertions that create the illusion of truth while failing to offer meaningful guidance to those tasked with making consequential decisions. Suppose the report’s conclusions about agents’ target beliefs have the characteristics of rules of thumb. In that case, analysts should acknowledge that those conclusions do little more than encourage attention to issues that may matter and that those tasked with making consequential decisions cannot assume the guidance of those conclusions will improve their odds of success. Suppose the report’s conclusions about agents’ target beliefs have the characteristics of imprecise beliefs. In that case, analysts should acknowledge that the guidance of those conclusions can do nothing more than increase one’s odds of success and that one cannot assume the guidance of those conclusions will make it likely that one will succeed. Finally, suppose the report’s conclusions about agents’ target beliefs have the characteristics of precise beliefs. Since the complexities of human behavior and institutional functioning make this degree of precision unlikely, analysts are advised to subject the processes that shaped their conclusions to a comprehensive critique. Only conclusions that survive such critiques should be offered as reliable insights into the future. Determine the likelihood/probability that the conclusions of your agent-focused CBA are correct. [4] Justify your estimate. Specify your degree of confidence that your agent-focused CBA is a “quality analytic product.” [5] Explain your view. 3. Document all analytic work on the Figure 6.3 worksheet and prepare the analytic narrative (written report, verbal briefing, etc.). Chapter 11 of Security Analysis: A Critical-Thinking Approach provides guidance on preparing the analytic narrative. [6] | ||

Figure 6.4 | Identifying the Desires Motivating Beliefs[7] | |

This questionnaire can be used to reveal the fundamental need(s) actually motivating the beliefs of agents and analysts. If the analyst responds to each item pair as they believe the agent would if they (the agent) were self-aware, insightful, and honest, this questionnaire can reveal what motivates the agent’s target beliefs. If, when critiquing their own beliefs, the analyst responds to each item pair with similar self-awareness, insight, and honesty, this questionnaire can reveal what motivates the analyst’s beliefs about their conclusions, including their beliefs about the agent. Belief to be examined (specify):

Keeping the to-be-examined (target) belief in mind, ask how the person holding the belief (whether agent or analyst) actually feels about each of the issues addressed by the pairs of contrasting statements below. In each case, the believer may agree or strongly agree with Statement “A,” agree or strongly agree with Statement “B,” or agree with neither statement. Concurrence with Statement “A” reflects a desire for reassurance, while concurrence with Statement “B” reflects a desire for competence (information). RESPOND TO EACH PAIR OF CONTRASTING STATEMENTS BELOW BY:PAIR #1

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #2

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #3

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #4

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #5

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #6

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #7

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #8

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #9

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #10

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #11

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #12

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #13

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #14

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #15

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #16

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #17

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #18

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #19

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #20

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #21

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #22

1 2 3 4 5 PAIR #23 a.I feel obliged to champion my belief, even if doing so requires me to portray biased information, falsehoods, or irrational arguments as unquestionable truths. b.I feel obliged to present my belief fairly and accurately, even if doing so creates doubts about its truth, its goodness, or the trustworthiness of its guidance. 1 2 3 4 5 Assessing the Fundamental Needs Motivating the Target Belief.TOTAL #1s CIRCLED OR BOLDED (STRONG AGREEMENT WITH STATEMENT “A”): TOTAL #2s CIRCLED OR BOLDED (AGREEMENT WITH STATEMENT “A”): TOTAL #3s CIRCLED OR BOLDED (AGREEMENT WITH NEITHER STATEMENT “A” NOR STATEMENT “B”): TOTAL #4s CIRCLED OR BOLDED (AGREEMENT WITH STATEMENT “B”): TOTAL #5s CIRCLED OR BOLDED (STRONG AGREEMENT WITH STATEMENT “B”): Beware of the temptation to interpret the results of this questionnaire mechanically. For example, one might assume believers (whether agents or analysts) look to a particular belief to inform them about reality if, upon examining their feelings about that belief, they find they agree or strongly agree with the majority of “B” statements. However, reflection on the paired statements comprising this questionnaire reveals that endorsing an “A” statement generally indicates the believer is passionate about the belief in question while endorsing a “B” statement generally indicates the believer views the belief with a degree of detachment. For this reason alone, those interpreting this questionnaire should weigh endorsements of “A” statements more heavily than endorsements of “B” statements. But there is an even more compelling reason for weighing endorsements of “A” statements more heavily than endorsements of “B” statements. Objectivity is inherently fragile; a single flaw in an otherwise valid argument can invalidate that argument. Bias, by contrast, is inherently durable. Adding a valid argument or observation to a flawed argument adds little or nothing to its validity. Thus, interpreting responses to this questionnaire requires imagining how the attitudes reflected in the endorsements are likely to impact objectivity. If those responses suggest the believer has the requisite commitment and discipline to treat the target belief objectively, the interpreter should classify the belief as informative. If those responses suggest the believer lacks such commitment and discipline, the interpreter should classify the belief as reassuring. And if those responses suggest the believer’s treatment of the belief vacillates, the analyst should evaluate the belief in question as two distinct beliefs — one informative and one reassuring. Conclusion (circle or bold one):

Justification/Evaluation (optional): | ||

- Michael W.Collier, Security Analysis: A Critical Thinking Approach. (Richmond, KY: Eastern Kentucky University Libraries, Encompass Digital Archive, 2023), free download at htttp://encompass.eku.edu/ekuopen/6/ (accessed June 1, 2023), chap 4.↑

- Ibid, chap 5.↑

- Ibid, chap 6. ↑

- Ibid, chap 11. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Barnet D. Feingold, "Barney’s Place, A new look at beliefs," http://barneysplace.net/site/ (accessed December 19, 2020), art. 7. ↑